Anaïs Nin’s life and legacy has had more ups and downs than a pogo stick competition at a school for hyper-active youths.

Critical appraisal of her works Delta of Venus, Little Birds and others was usually vicious and largely dismissive most of her life.

When her novel, Spy In The House of Love, came out she hosted a party to which she invited a score of critics. None came.

But Nin pressed on, making for herself a place in the history of letters, following much the same strategy as Bellerophon, in the John Barth’s novel Chimera, who becomes a mythological hero, despite the odds, by doing what mythological heroes must do.

Nin joined the circle of artists and writers in Paris, impressing them if not with what they found between the covers of her books, then with what they discovered beneath the covers of her bed.

Her hold onto a certain prominence, mixed with a healthy helping of notoriety was cemented by her long time relationship with Henry Miller whom she met when he was a bald middle-aged, unpublished writer of his Munchausen-like sexual escapades.

Perhaps Nin saw a kindred soul, but whatever the reason she took it upon herself to support him for the next ten years so he could work on Tropic of Cancer, the book that would bring him both fame and infamy.

Nin’s list of lovers is impressive as well as troubling: Salvador Dali, Antonin Artaud, Otto Rank (while he was her analyst), John Steinbeck, Lawrence Durrell, Gore Vidal (more in wish than fulfillment) and even her own father, Joaquin Nin a pianist of some renown, in an affair that began when she was in her twenties.

In the end it was not her writings but her life that gained Nin the recognition she sought.

It came in 1966, when she was in her sixties and living in Los Angeles, with the publishing of The Diary of Anaïs Nin in multiple volumes, taken from the journals she had been faithfully keeping since the age of eleven and which amounted to some 15,000 typed pages.

Anaïs — A Dance Opera succeeds not due to the overwhelming excellence of its parts, nor for the merits of its core narrative. There are weaker aspects of the show capable of dragging the work down, and aspects of strength within the piece that, if care had not been taken, could have threatened the whole piece with capsizing.

But producer Ryan Bergmann with the show’s co-creators Janet Roston and Cindy Shapiro has fused a harmony into the discordant elements.

Director Roston caresses a steady pace into the piece that never allows the show’s 90 minutes to drag

If in serving double duty as the show’s choreographer, Roston’s limitations may be somewhat perceptible those limitations are fortunately not allowed to be blatantly present.

Co-creator, Shapiro wears two hats as well, bearing responsibility for the music and lyrics.

Again, we have a “push-me/pull-you” in the sense of unequal output.

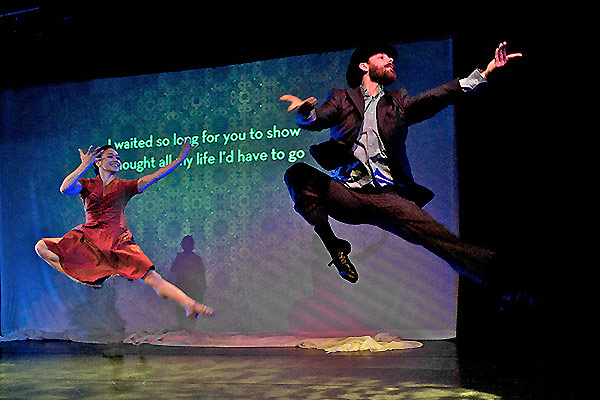

Shapiro’s score has variety and craft, but too often her lyrics are reduced to mere repetitions – the worst offender is “To The Edge” the stanza-section dealing with writer Henry Miller.

The show is a hodgepodge of conflicting components, however its salvation was found in the intelligent blending of those elements into what is, if not an enlightening evening, one that is very entertaining and lovely to behold.

Whether credit goes to Bergmann or Roston or their alliance what could have been a Mulligan Stew has been served up as a refined bouillabaisse.

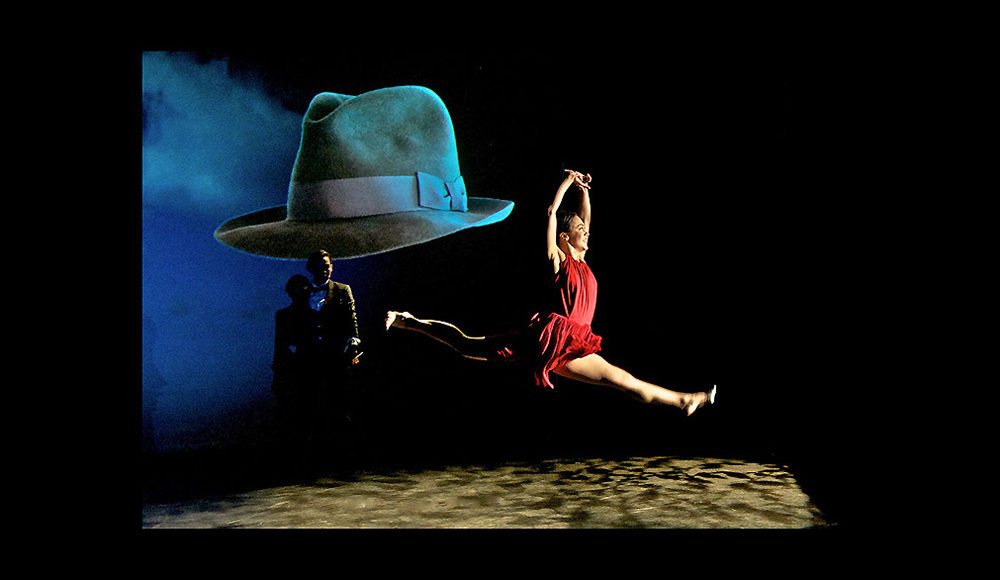

The strongest aspects of the production are the projections of Joe LaRue and the choreography of Roston, whose limited vocabulary is superseded by a superb troupe of dancers.

These factors could have easily smothered the thin lyrics and even thinner narrative had attention not been given to the crafting of the work into a serviceable whole.

The strongest block of the production is the opening of the second act, featuring the two most fully realized stage stanzas of the seventeen which constitute the show; Café Culture illustrating Nin’s introduction into the cafés of Paris and the intelligentsia who frequented them, and Delta of Venus which takes us through Nin’s ceaseless sexual adventurism and her time as a writer of pornography. (Undertaken in order to support Miller in his writings.)

The cast is solid and talented.

Madison Dewberry, is the sole live voice on stage, in the role of the “Eternal Anaïs” a hybrid of “The Stage Manager” in Own Town meets the “MC” in Cabaret. Micaela DePauli embodies the physical Nin as a spirit of dance, and even bears a passing resemblance to her subject.

Dewberry and DePauli cannot be faulted in their performances save in wishing those performances had been more challenging.

Michael Quiett has moments, but while Roston’s choreography succeeds in reflecting Nin’s persona the same can’t be said of her approach to Henry Miller.

Miller was a sexual jokester disguised as a strutting penis who dominated Nin’s life for nearly a decade. We need to see the force on stage that so beguiled Nin in life and we don’t.

Denise Woods is also to be commended on both her languid sensuality on stage, and for not using it to steal the show.

Anaïs — A Dance Opera should not be approached as a character study, as it skims over the more troubling features of Nin’s life and declines to plum the depths of what is presented.

But if taken as a celebration of an individual who conjoined her sexuality and creativity in an aura of unfettered wantonness and an almost childlike wonder then you’re sure to feel passion’s heat from this show.

Anaïs — A Dance Opera

on now at the Greenway Court Theatre

has been extended through Saturday, Sept. 24.

544 North Fairfax Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90036

FREE PARKING in the lot adjacent to the theatre

Box Office: (323) 673-0544

Or CLICK HERE for Tickets and Additional Information