It is not with eyes alone that we read a novel’s passage or play’s scene; we read them through the grinded lens of culture and the glass of moment.

Some times these “bi-focals” bring the matter read into a startling clarity never appreciated before, with new aspects revealed.

On other occasions we may find the lines blurring, becoming all but unreadable. And so authors once celebrated as paragons of the craft find themselves and their works faded from relevance and cultural consciousness, while other authors, whose works were dismissed as of minor merit and themselves resolvedly neglected, find their star in ascendancy.

Time also has its affect on how characters within works of literature are interpreted. Once Shylock was viewed as a comic villain for whom no tears were shed, and Portia a figure to be admired, perceptions which have altered in today’s readings. —

Lolita, Daisy, Ophelia: A Love Story is a well-structured and refreshingly thoughtful, short one act that draws on this phenomenon to fuel a restatement of feminist goals; a restatement that gives over perhaps to a rather barbed assessment of those goals.

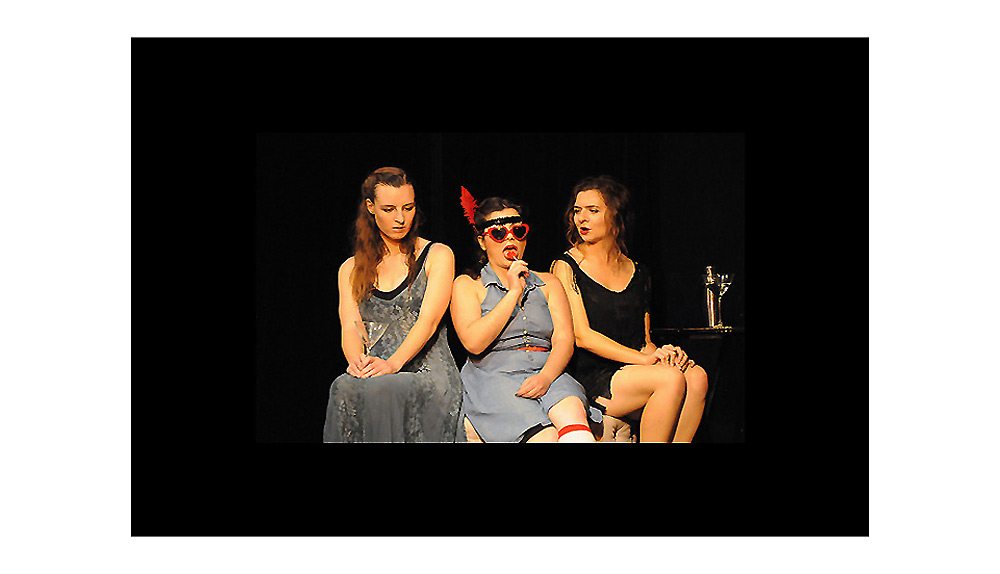

In a darkened, indeterminate arena three, feminine icons engage in a repetitious recital of the roles in which they serve. They respond to a disembodied male, engaging it in a ritualistic rendering of the same words, with the same inflections time after time until abruptly – the voice stops. And now for the first time, suddenly cut off from the secure male mooring, they suddenly become aware of one another.

There is the coquettish twelve year old Dolores Haze (Leah Artenian) with her heart-shaped sun glasses and lollipops; called “Lolita” by Humbert Humbert whose withering obsession with her is at the center of Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel.

Regally draped over a chaise lounge, aloof and alluring, is Daisy Buchanan (Savannah Gilmore), for whom the mysterious millionaire in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby has reinvented himself and manufactured, with his wealth, a surreal, Jazz Age “Magical Kingdom” which he hopes to lure her into.

Fitzgerald with his slim volume is a perfect paradigm of the changeable nature of cultural preferences; in 1925 The Great Gatsby was a failure, selling barely 20,000 copies. Today it is regarded as one of the great works of American literature.

Lastly there is Ophelia (Sophia Brackenridge), from William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. Abandoned by her brother, discarded then abused by her lover, manipulated and exploited by her father, she plunges first into madness and then to her death in a swiftly running stream.

Suddenly isolated from the roles they have always played, and more importantly, out from under the shadows of the men in their lives, they turn first to explore the confines they share, then one another –

“You talk like you’re in a book,” Lolita exclaims to Ophelia.

Their discussion turns to the roles they are forever forced to occupy, and the men that dominate their lives.

“No one ever cared about my American dream.” Daisy moans.

“My story is his diary, how awful is that?” Lolita bitches.

The three actresses in the roles of women freed from their roles, all turn in outstanding performances. Brackenridge with an airy hesitancy that speaks to how near the surface madness lies. Gilmore conveys the distain that comes with the scam prestige of old money. Artenian succeeds in bringing the petulance of youth to the stage and manages nicely in making the audience overlook her age which is wrong for the role.

While the actresses are all successful in their performances, the greatest success on stage is that of the play itself. Here is that most untrustworthy of all efforts in the theatre, a project self-generated and self-directed by the actors themselves.

Generally there is no more painful evening than sitting through such a production usually lacking any specific direction and embarrassingly self-indulgent.

Generally there is no more painful evening than sitting through such a production usually lacking any specific direction and embarrassingly self-indulgent.

Not here.

Typically such performances are structured with the individual actors focusing on their core character and then the company joining to intertwine the pieces into a whole; with the results usually less than satisfying.

The Moirai Theatre Company has succeeded where so many others have failed.

There are some parts stronger than others, Brackenridge especially has some excellent moments, but as a whole the play worked wonderfully well, highlighted by the three women engaging in a dance in celebration of this new found freedom.

Of course, as they must, the time comes when the three must return, however sorrowfully, to their roles.

So the play ends as it began, with each reverting to their parts.

At first, the ending disappointed me. The three just returning to their “roles” repeating the same lines again, as I was looking for some change some growth in their characters; but upon reflection I think I may have missed it.

Perhaps it is not for the roles themselves to reflect the change of their growth, perhaps it for us, as a society to do that.

That is, if as a society, we have grown.