The Algerian War, 1954-1962 is a struggle, all but, forgotten today in the West.

For brutality, employment of terrorism, and the pitting of Muslim against European interests, on the surface, it seems painfully familiar. But it was so much more. Algeria was “French” to France, and was “France” to the French whose presence had a 124-year history. It was not a conflict like we have with Iraq today; it was more like our revolution from the British Empire, only the separation between France and Algeria was the scant blue Mediterranean and not the daunting Atlantic. To the French, in 1954 the demands of the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) for “restoration of the Algerian state,” was akin to Alaska attempting to succeed from the United States.

But years of restricting the economic and social opportunities of the Muslin population, and the refusal to initiate even the slightest of reforms made—as history continual shows us—the avoidable conflict, inevitable.

The Algerian War was not one revolution, it was many. It caused the fall of six French prime ministers and the Fourth Republic, and brought France to the verge of civil war. It lead to 900,000 Pied-NoirsÙ and upwards of 200,000 “loyal” Muslims fleeing Africa for France, an exodus whose ramifications are sadly apparent in the Charlie Hebdo attack. And with Algeria’s victory over the colonialism of the past, the seeds were sown for Islam’s future confrontation with itself.

In the national elections of December, 1991, the FLN dominated government of Algeria faced defeat at the hands of the Islamic Salvation Front, whose radical Islamist program included the dismantling of the secular, semi-democratic state. A crisis ensued and elections were cancelled triggering eleven years of Civil War resulting in 100,000 to 200,000 Algerian deaths, in what would prove the first “revolutions” involving Islamic identity within a state structured on the European model.

It would not be the last.

What little exposure most Americans have had to the Algerian conflict has come from two films.

One is the original The Day of the Jackal (1973) the Fred Zinnemann film starring Edward Fox as a professional assassin known only as the Jackal who is contracted to kill Charles de Gaulle, the President of France. Author Frederick Forsyth based his fictional tale on a foundation of fact, opening his novel with the story of the actual attempted assassination of de Gaulle on August 22, 1962 carried out by Jean Bastien-Thiry, a renegade French military officer (whose execution by firing squad the film features as well). What is not made fully clear in the film however is that the reason behind Bastien-Thiry’s attempt was de Gaulle’s decision to grant independence to the Algerians.

The other film is director Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966), which is enjoying a good deal of press these days due to the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of its release.

Pontecorvo’s film is powerful in its story and unique in its making.

The pseudo-documentary approach caused the film to be released in the USA with a disclaimer printed on all the lobby posters assuring audiences that not one foot of newsreel footage was used, putting the minds of American audiences to rest that they were seeing a real “war movie” and not being duped into suffering through some “New Wave” picture with all that annoying art business foreigners liked in their motion pictures.

The film’s structure can be appreciated as a celluloid triptych of factual events whose “proximity” serves for a representation of the conflict in total.

The focus of the opening panel was taken from the memoirs of Yacef Saadi, whose memoirs were a partial source of the film. January of 1957 saw a further amplification of hostilities in the three-year-old conflict. The success of the FLN retaliation against French army personnel and “loyal” Muslims led to the severity of France’s response and the guillotining of FLN members. The task of an Algerian’s reaction to these reprisals fell to Yacef.

Yacef gathered about himself a group of young attractive Muslim women—daughters from the city’s small Arab bourgeois—some were nurses, others law students, but all shared a deep devotion to the Algerian cause. At Yacef’s instruction, three of the young girls would do their hair in the latest Parisian styles and don the breezy, bright summer dresses popular with French Algerian girls. Then they were each assigned an address and given a beach bag. In the bags, buried beneath sun tan lotion, towels, glossy magazines and bikinis was hidden a small bomb.

The destinations of the first assault would be an ice cream parlor where mothers and their young children flocked on the hotter days, a dance club popular with students, and a terminal at Air France. The blasts would be timed to go off one minute apart. Yacef would openly weep learning of those killed or maimed in the blasts, but the bombing campaign continued.

The film does not go into this particular detail; that is the story of Djamila Bouhired, one of the original “girl bombers” who would be captured at a later date. Imprisoned by the French and tortured, she refused to give away any of her comrades.

Next in sequence is the account of Colonel Matthieu, based partially on General Jacques Massu of the French 10th Parachute Division, who was given the task of rooting out the FLN and applied a methodical viciousness to the undertaking. It is to the credit of the filmmaker that the French, even Matthieu, are not presented as evil incarnate, while the FLN are shown as men willing to go to any extremes and not sanitized as virtuous freedom fighters.

The threads converge in the third story of Ali La Pointe.

Ali, whose real name was Ali Ammar, was a petty criminal recruited to the cause while in prison. He would become one of the FLN’s most trusted lieutenants, carrying out numerous “executions” on the streets of Algiers in broad daylight.

He would also become one of the revolution’s most celebrated Martyrs.

Acting on an informer’s tip French paratroopers trapped Ali in an Arab tenement in the Kasbah. With him would be Hassiba Ben Bouali one of the girl bombers and Yacef’s 12-year-old nephew le petit Omar (Little Omar). Demands were made for their surrender and deadlines given.

It was said Little Omar passed the long hours snipping, and playing with, paper cut outs.

The French paratroopers spent their time planting powerful explosives all about the complex.

When the deadline arrived, they detonated them. Their blast ignited a FLN weapons stockpile and the combined explosion was powerful enough to reduce the entire structure to rubble, killing not only Ali and his cohorts, but 16 other Algerians, including four small children the paratroopers had neglected to evacuate from the tenement.

On this tragic event Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers ends.

In making the film Pontecorvo used only one professional actor, Jean Martin in the pivotal role of the French Colonel Matthieu, with all the other roles being cast from non-professionals who were hired due to their resemblances to the characters they played.

With one exception, Yacef Saadi plays himself in the film.

Here we leave the film and return to the history.

After the war, Djamila Bouhired, the girl bomber captured by the French, was released from Prison and returned to Algeria.

In his classic study of the conflict, A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962, Alistair Horne* writes in the final chapter: “Djamila Bouhired, married her defending lawyer, then divorced him….”

There’s more beneath those 55 letters than one can begin to imagine.

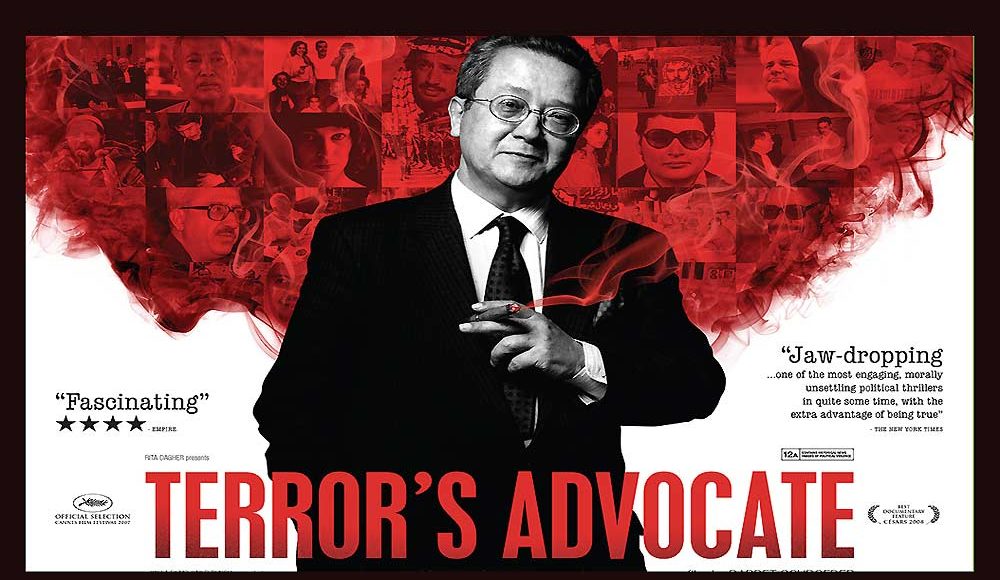

Director Barbet Schroeder’s 2007 documentary Terror’s Advocate can be viewed as the sequel to The Battle of Algiers, and the story it tells serves as a Rosetta Stone that connects and reveals the history of terrorism stretching from the ’60s to the present.

The subject of his documentary is also the subject of Horne’s 55 letters; the French lawyer Jacques Vergès.

Born in 1925 in Thailand, the son of a French diplomat and Vietnamese mother Vergès was the embodiment of European colonialism, the union of two separate cultures.

After World War II Vergès would move to France, studying law at the University of Paris; a gourmand with a fine palate, and connoisseur of expensive wines, Vergès would epitomize the ideal of the urbane, sophisticated Parisian. Yet due to his dark Asiatic features he always found himself subjected to the petty prejudices of the time.

Vergès would seek his retribution for these insults in the courtroom.

It was during the Algerian struggle that Vergès first gained notoriety in France, which he did by taking for his clients those who most French lawyers

refused to defend; a practice he would follow for the entirety of his career. His fame was achieved however, not just by his choice of clients but, by his defense of them.

A supporter of the armed struggle against France in Algeria, Vergès took on the representation of Djamila Bouhired, who was charged with planting the bomb in a café that killed eleven people.

Vergès was expected to follow the standard course taken by lawyers at the time, which was having the client admit guilt and throwing themselves on the mercy of the court.

But Vergès didn’t plead to the charges, he denied them.

Vergès mocked, and derided both the judges and prosecutors, comparing the French presence in Algeria to the Nazi occupation of the 1940s, and painting Bouhired as the patriot.

In what Vergès would later refer to as the rupture strategy, he used his combative and disruptive method to put France itself on trial before the jury of world opinion, while fashioning Bouhired into the face of the revolution.

Nevertheless, the court arrived at a verdict of guilty with Bouhired being sentenced to death. For the judges the case was over, but not for Vergès who continued the trial in the national press until public pressure forced a pardon for Bouhired which was followed by her release from prison.

And as Horne wrote,

“Djamila Bouhired, married her defending lawyer.”

Now an international symbol of revolution, thanks to Vergès, the couple would be invited to China to meet with Mao. Vergès would also be instrumental in facilitating China’s tentative ingress into the geo-political sphere of Africa, whose dominating presence today on that continent should be viewed by both the international community and this nation with far greater apprehension than it is given.

In Terror’s Advocate, Director Schroeder gives us a compact history of terrorism over the past fifty years, and does so through the career of Jacques Vergès.

Perhaps the most extraordinary revelation of the documentary is the affiliation of groups both left and right: a Swiss Nazi funds Palestinian terrorist teams, The Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) is tutored by the Palestinians, the Japanese Red Army Allies itself with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the Iranians shelter members of the Italian Red Brigades.

And always at the center of this storm one finds Jacques Vergès.

Vergès’ work was often carried on behind the scenes, but his roster of clients reads like a list of Satan’s Facebook friends: Ilyich Ramírez Sánchez, alias Carlos the Jackal, Tariq Aziz, Saddam’s Vice President, Mahmoud Hijazi of the Palestinian Fatah movement, Holocaust denier Roger Garaudy, he offered his services to Slobodan Milošević, Dictator of Serbia and defended Khieu Samphan 3rd ranking member of Pol Pot’s government responsible for the murder of two million of his countrymen.

Vergès even took on the defense of Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo SS-Hauptsturmführer, known as the “Butcher of Lyon” who, while stationed in France, was responsible for some 14,000 deaths.

He told his client, “You’re not innocent, but neither are you a monster. You’re an officer … of an occupying army in a country that resists. You’re no better and no worse than a French officer in Algeria, an American officer in Vietnam, a Russian officer in Kabul.”

During that trial, asked if he would defend Hitler, Vergès’ replied with a smile, “I’d even defend [George W.] Bush. But only if he agreed to plead guilty.”

There is an old adage:

“All politics are personal”

Schroeder’s documentary leads us to believe so is all terrorism.

Vergès and Carlos the Jackal partied together and even shared a lover, he was a welcome guest in the home of Waddi Haddad the father of modern terrorism, and he was a school chum of Saloth Sar better known to the world as Pol Pot.

Vergès’ life is the stuff of John le Carré novels the full mystery of which even Schroeder’s Terror’s Advocate is unable to unravel.

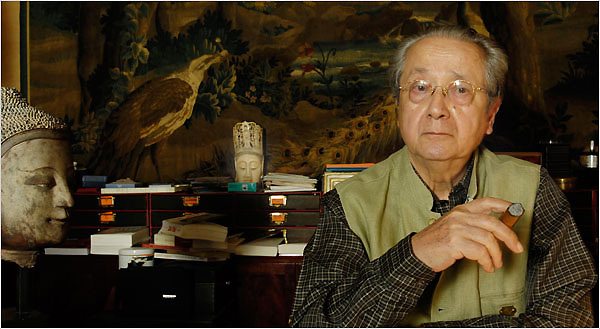

Jacques Vergès sits in his office, trademark cigar in hand, surrounded by works of art: gifts from clients. (Photo by Helen Margaret Giovanello / Courtesy of The New York Times)

But it is still a fascinating history of our turbulent times consisting of interviews with former terrorists, friends of Vergès, his former lovers, national security officials, clandestine tape recordings done by East Germany’s secret police the Stasi during the cold war, old newsreels, failed assassins now in hiding, journalists, historians and exiled leaders of the Khmer Rouge in the remote jungles of Cambodia.

Yet the focus always returns to Vergès in his opulent Paris apartment seated behind a luxurious Kingwood desk, with rich Renaissance tapestries hung on the walls and a Havana in his hand.

Of all the faces of terrorism imaginable, perhaps this one is the most chilling.