Whether you view the later works of Irish playwright and novelist Samuel Beckett as avant-grade, Theatre of the Absurd, tragicomic minimalism or a dramatic con job, they do provide an intriguing Rorschach experience for any audience.

The Odyssey Theatre’s Koan Unit created an evening aptly enough entitled, Beckett5 that opened with four of Beckett’s shorter works and closed with one of his best-known pieces.

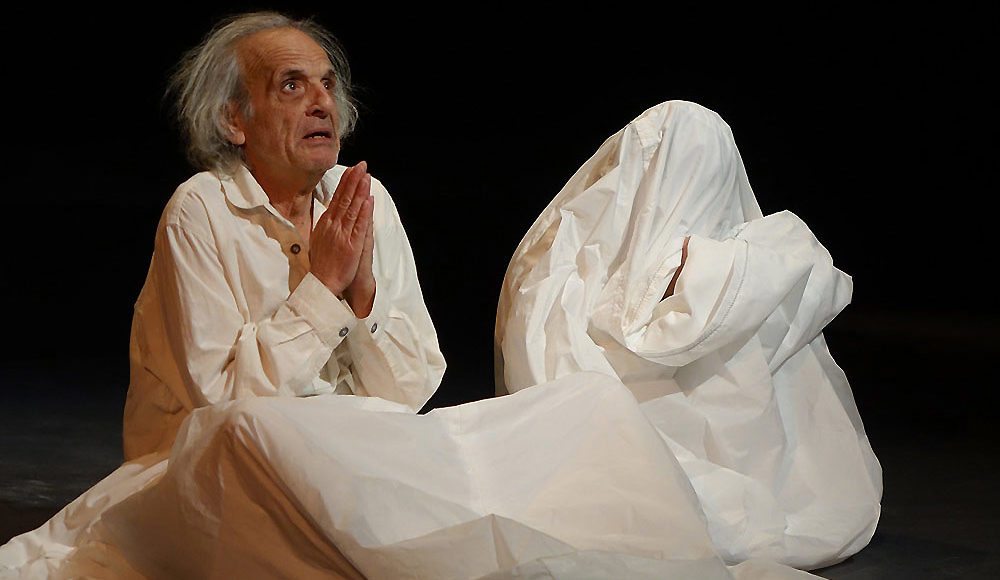

Act Without Words II (written in the late 1950s), one of Beckett’s few mime pieces, opens with two sacks and a pile of clothes on stage.

The “Goad”, a shadow player with a long pole, pokes at the first sack and awakens “A” (Alan Abelew). “A” rises unsteadily and hesitantly meets the day. Going to the pile of clothes he dresses with difficulty, eats a breakfast consisting of a puny unappetizing carrot, and drags both sacks one foot to stage right. That ends his “day.” He readies for bed, dumping the clothes he wears back into a pile, climbs into his sack and silently prays, mouthing the words, “Help me” before disappearing into the folds of his bag.

The “Goad” then prods the second sack awaking “B” (Beth Hogan). “B” greets the day with enthusiasm, dresses with great care and some pride, and feels a sense of purpose when she pulls her and A’s sack another foot towards stage right. Then content with her accomplishment, she undresses with great care then disappears back into her sack.

The “Goad” then prods…..

The piece is an abbreviation of a reoccurring Beckett theme, that regardless of one’s individual attitudes or desires, life demands that you live it.

Come and Go was written in 1965, and Beckett invented a word for describing it: “dramaticule,” meaning a very, very short play.

It was Beckett’s habit to first write his plays in French then translate them into English. With Come and Go there was an additional linguist layer added on, being that it was first performed in German, so depending on which translation you refer to it runs between 121 and 127 words.

The plot is as sparse as its lack of verbiage: three childhood friends, Flo (Hogan), Vi (Diana Cignoni), and Ru (Sheelagh Cullen), sit on a bench staring out at the audience.

The play is rippled by Shakespearean undertones starting with Vi’s opening line— “When did we three last meet?” —harkening back to Macbeth’s witches. Then there are the characters’ names which echo Ophelia’s madness. “Flo” for flowers Ophelia handed out. “Vi” for violets, which symbolized faithfulness and “Ru” for rue, symbolic of bitterness and which was thought to induce abortions at one time.

Beckett, notorious for his lengthy stage directions, outdid himself with Come and Go, providing not only stage notes that exceeded the play itself, but numerous diagrams for every aspect of the staging right down to how the three women are meant to hold hands at the end.

Age is the under current here, with the three women holding hands and Flo’s closing line, “I can feel the rings” a distinct reference to old growth forest.

Catastrophe, written in 1982, was dedicated to Czech playwright Václav Havel who was then imprisoned in his homeland. It has been called Beckett’s most political pieces, which I can understand, as well as one of his most “optimistic works” which I can’t.

A dictatorial Director (Hogan) bullies her Assistant (Abelew) as they add the final touches to a display they will soon be presenting. The display consists of a brutalized and cowering Man (Norbert Weisser) standing on a small platform.

As the Director demands changes, the Assistant either takes notes or removes the man’s clothing and, in doing so, reveals bleeding wounds on him.

Finally, the Director is pleased with the effort and voices her confidence that when presented it will have the audience “on their feet.”

Leaving the man alone, the stage fades to blackness as we hear the audience roaring their approval.

Dedication aside, I’ve never seen this as a political play so much as a commentary on the fate of spirituality in our society.

The Director and Assistant did not ring totalitarian so much as biblical, with the perspective of Old and New Testament, one giving out ruling/prophecy while the other tries to match it for validation of legitimacy.

That the unseen “theatre Technician” with whom the Director has a short exchange is named Luke has resonance, being that he shares the name with the third gospel in the New Testament and the one most concerned with attesting to Jesus’ status as the messiah*.

Also, the fact that Luke the Technician is rehearsing the “lighting” of the “Man,” and the Director’s concern that the feet be seen, which they always are in depiction of the crucifixion, points in this direction. The statement is on the exploitation of those who would be genuine martyrs, and Beckett seems to support this view in a statement he made to a theatre critic, that…

“He is a triumphant martyr rather than a sacrificial victim.”

Spirituality suffers at the hands of the masses.

Jesus may have started out as a “messiah,” but three nails later he’s reduced to jewelry.**

Closing the first act is Footfalls: Written in 1975, it was first performed at the Royal Court Theatre with Beckett directing Billie Whitelaw for whom the piece was written.

His inspiration for the work came from a conversation with a woman, the daughter of an old friend, who told him of her struggles with clinical depression, and therefore was well suited for Beckett to utilize one of his favorite devices: the exposed internal dialogue.

In this piece, the dialogue is between the pacing “M” (Cignoni) and the disembodied voice of her “Mother” (Cullen). Like the best of Beckett’s works, the plot is threadbare to the primacy of the playwright’s objective.

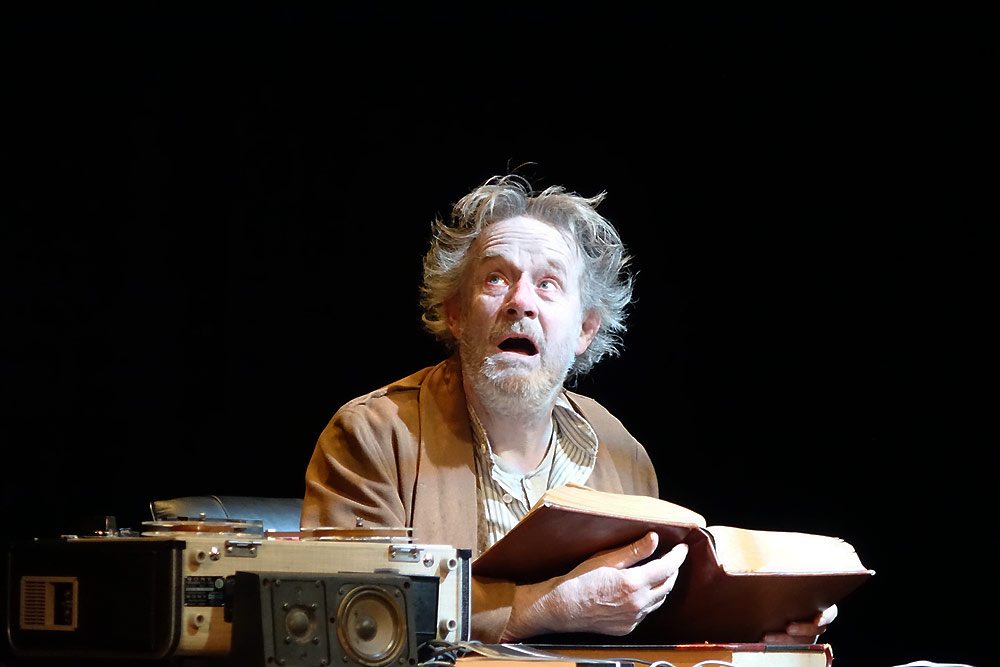

The second act opens on Krapp’s Last Tape.

Inspired by the actor Patrick Magee’s*** radio readings of his novels, Beckett wrote Krapp’s Last Tape specifically for him, between 1957-58.

All of Beckett’s works carried the aforementioned “Rorschach experience,” but this short piece about a man reviewing the tapes recorded for himself thirty years earlier, shoulders a prodigious amount.

I have seen it explained as an absurdist treatment of Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson” to a repudiation of the Manichaeistic world view.

I think it is simply what it appears: a man confronting himself over a bog of three decades.

It is encouraging, I believe, that the Odyssey has chosen to open its 2017 season with this production. It has the feel of the mythical giant Antaeus, who drew his strength from whenever he touched his mother earth.

For the Odyssey the earth is Beckett, Pinter, Ionesco, Kafka and their fellow travelers.

This statement finds validity in the solidness of the productions, and Beckett5 is a thoroughly solid evening of theatre that has moments of pure excellence.

The Koan Unit consists of talented actors, who, under Ron Sossi’s tutelage, are acutely adept at handling some of the most difficult theatrical styles, and that ability is on display here.

Beth Hogan can do no wrong….well, she probably can, I’ve just never seen it. In both Catastrophe and Come and Go she weaves her presence into the fabric of the works, but it is in Act Without Words II, where both she and Abelew show the temper of their talents.

Most half way capable actors can do something with a finely engraved character and perfectly crafted dialogue.

But when a playwright lobs a bare concept on stage, that’s when you separate the true actors from the prime time bubble gum.

Abelew opens the show on a high note, and benefits from having a physicality that is almost a perfect fit for Beckett.

And Norbert Weisser closes Beckett5 on a note high enough to require NASA take it into consideration for its upcoming launches.

In his silence during Catastrophe and in Krapp’s duel dialogue he fills the moments with the muted cataclysmic rumbles of all humanity. One of my earliest memories of being overwhelmed by the power of theatre was watching him perform with the Provisional Company. He is a talent we can never see enough of.

As for Mr. Sossi’s direction, there is no flaw to be exposed.

Mr. Sossi has a genius for theatre and, given the challenge of Beckett’s material, that genius is given the opportunity of going nova.

With the easy dismissal of the gender swap of Catastrophe and the substitution of a shadow actor for a pole on wheels in Act Without Words II, Sossi achieves a purity of staging that would have brought a smile to Beckett’s face (No small feat that!).

From the “metronome” quality of Come and Go, to the deep delving into the nature of despair in Krapps’ Last Tape, Mr. Sossi orchestrates the evening like the maestro he is.

So good job of kicking off 2017, and all the best to Ron, Beth, Sally, Lucy, Michael, Mark and all the good folks at the Odyssey.

♦ ♦ ♦

The KOAN Unit Presents:

Beckett5

PLAYING NOW THROUGH March 4

at

The Odyssey Theatre

2055 S. Sepulveda Blvd.

Los Angeles CA 90025

For Tickets and Additional Information:

(310) 477-2055 ext. 2

or

* There are only two places in the New Testament where Jesus is called “Savior” one is John 4:42, the other is in Luke 2:11.

** For those interested, there is a rather good film version of Catastrophe in the Beckett on Film Series. Directed by one playwright, David Mamet, it featured another, Harold Pinter, in the role of the Director. It also boasts the last screen appearance of the legendary actor John Gielgud in the role of the Man. Scant weeks after the filming, Gielgud would be dead.

*** Perhaps best known to American audiences for his part of Mr. Alexander who is forced to watch his wife’s rape in A Clockwork Orange.

Support the Voices of The TVolution. Please Subscribe.