By Ernest Kearney — Okay, leave the statues alone.

I know, you’ve already started to pigeonhole me as some mouth-breathing, Tiki torch hoisting knuckle dragger; but you’re off the mark.

I’m a big mouth white guy of Irish descent who, most likely, has ancestral ties to former President Barrack Obama, and that statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, and those statues of Jefferson Davis and P. G. T. Beauregard in New Orleans; they all belong to me.

Those statues in Charlottesville and New Orleans belong to my editor Darwyn C. a black woman, with family still in her home town of Denver and a nephew who has toured the world as a member of a renowned Celtic dance company.

Those statues belong to my friend Josh S. a Jewish guy from Philly who after working his ass off for about six years starting up a pretzel company, made his first million and transferred his political affiliation to the Republicans.

Those statues belong to my wife Marlene, a seventh generation Angelino who bears the bloodline of Aztec royalty in her profile.

Those statues belong to my old roommate Colin G.; formerly a Brit art critic presently a naturalized college professor in Northern California.

Those statues belong to my friend “Trash” ex-con, Nam Vet and biker who writes pretty good poetry.

They belong to my friend Bo a computer junkie and native of South Korea.

They belong to my friend Jim F. gay retiree and former Universal Tour Guide.

They belong to my friend Gybi who is in Southern California studying to be a psychiatric nurse and is a prince back in Ghana.

They belong to my niece Veronica who I neglected to call in order to write this, they belong to my friend Lily S. who missed the last play I produced because it coincided with Ramadan, they belong to my friend Jim L. who is still trying to defend voting for Trump to me and to my political fellow traveler Jules B. who just lost his “long time companion” Don M.

Unveiling of the Equestrian Statue of Robert E. Lee, May 29, 1890. Richmond, Virginia. (Sculptor, Antonin Mercié) (via Wikipedia)

Those statues in Charlottesville, New Orleans and elsewhere in the South are our history and, as such, belong to all Americans.

Even if you don’t want them, like it or not those statues belong to all of us –

They are not the exclusive property of David Duke and the rest of those marching miscreants.

Let me give you my reasons for this rather unpopular stand – and then I’ll give you my solution to the problem.

First and foremost, I don’t think those statues should be removed, because I don’t believe a nation’s history should be retailored to fit the constantly shifting fashion of society.

Now this does not apply to those monuments the likes of Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi or Felix Dzerzhinsky. When Dictatorships fall so should their symbols by way of purging the soul.

But when the statue of Charlie Chaplin in Hollywood was moved to a less conspicuous location in 1972 because of lingering hostility regarding his political views I was outraged. I disagreed with the statues of Gambetta, Rousseau and Jean-Paul Marat being carted off to seldom visited parks by the authorities in Paris when the political climate of that city took a sharp turn to the right.

And even though I would have been rooting for the rioters, I’m displeased that Chicago removed from its original site the memorial honoring the seven police officers killed by a bomb during the Haymarket Riot on May 4, 1886.

And I think it was wrong of Penn State to “disappear” the bronze of Joe Paterno. (I’ll get letters for that one.)

Believe me, I can understand why those statues and the one in Charlottesville would upset and disturb some. Because they’re opposed to bigotry, and police brutality and sexual assault and these are right beliefs.

But right beliefs should not foster foolish actions, or what I like to call the “Pirates of the Caribbean Bungle.”

I’m not speaking here of the celluloid lobotomies starring Johnny Depp, I’m referring to the classic Disneyland attraction, the very last one that Walt himself had a hand in designing before his death in 1966.

A year later the ride opened in the Magical Kingdom.

You’d climb into the boats at Laffite’s Landing as the fireflies flickered about you, float pass the rickety houseboats to the soothing stridulations of crickets, only to plunge down the darkened waterfall and suddenly it’s –

“Strike yer colors, ye bloomin cockroachers, by thunder we’ll see ya to Davy Jones!”

Cannons booming, cannonballs whistling and pirates pillaging the port of Puerto Dorado on Isla Tesoro in their frenzied search for booty all to the rousing chorus of “Yo Ho, Yo Ho, A Pirate’s Life For Me!”

But something you may not be aware of; the ride has been altered from Walt’s original design.

You see he had the pirates doing…well pirate stuff.

Threatening to drown the mayor unless he hands over the treasure;

Auctioning off female captives;

Putting the town to the torch;

Chasing wenches.

Well after 30 years of those pirates pursuing the damsels, it suddenly occurred to some Disney executive what the pirates had in mind once they finally apprehended those fleeing females.

So in 1997, kowtowing in the most inane fashion imaginable the Pirates received a PC makeover.

And all the distressed damsels were given heaping platters of yummy goodies that had the hungry pirates dying to sink their teeth in…. Yeah.

Secondly, history is deeper than most people realize.

Now Marlene holds very strong opinions about Robert E. Lee, she feels he was a traitor to his country and should have been hanged after the war. It’s a topic guaranteed to plunge us into a royal argument.

Few men are better than their times, and Lee was a man of limited imagination except on the battlefield. He opposed slavery as an “evil in any country,” but could foresee no remedy for that evil nor conceive of the black man as his equal.

He was a great general in the war, but it was in defeat that he became a great man.

After his surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in April of 1865, Lee rode back to his army’s camp, where upon some called on him to steal away to the mountains and continue the struggle as guerrilla warfare. Lee refused. The war was over he insisted and told his army,

“I have done the best I could for you. Go home now, and if you make as good citizens as you have soldiers, you will do well, and I shall always be proud of you.”

In his memoirs, Grant wrote of Lee,

“…there was not a man in the Confederacy whose influence with the soldiery and the whole people was as great as his.”

Lee saved this nation from a bloody Balkanization that it is doubtful we would have survived.

That alone deserves a statue in my opinion.

What of the other Confederates with memorials honoring them, those whose reputations are stained by their actions?

There are three statues, of which I am aware, in the United States honoring Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. One stands on private property in Nashville, a particularly shoddy depiction worked in fiberglass.

Now there’s a home in my neighborhood where the owner has gathered on his rather narrow lawn about twenty-five life sized bronzes of elephants, gorillas, giraffes, lions and other wildlife.

It looks as if he were trying to imagine the waiting terminal for Noah’s ark.

I don’t like it much, but like the kitschy fiberglass Forrest in Nashville, a man’s home is his cheesy castle.

The second statue of Forrest is in a cemetery in Rome, Georgia.

The third and most grandiose is found in the Memphis, Tennessee Park that bears his name and is the resting place for both him and his wife.

Forrest was perhaps the most feared cavalry leader the Confederacy produced. Grant called him “that devil Forrest.”

There are two great stains against his name.

The first is the Fort Pillow Massacre of Henning, Tennessee, where Forrest allowed his forces to kill hundreds of black Union solders and white Southern Unionists after they had surrendered.

Then there was Forrest’s early support and membership in the Ku Klux Klan for which he served as his region’s Grand Wizard.

It would seem cut and dry that Nathan Bedford Forrest no more deserves a statue in this country than does John Dillinger.

Yet the waters of history tend to be murky.

Forrest came to view the conduct of the KKK with some trepidation. After a year as Grand Wizard he issued an order to try to stem the violence against blacks by robbing the clan members of their anonymity by ordering that their masks and costumes “be entirely abolished and destroyed.”

The violence did not stop however, and in 1874 after the murder of four black men, Forrest wrote to the Governor of Tennessee volunteering

“to help ‘exterminate’ those men responsible for the continued violence against the blacks.”

He extended his services to the state

“to exterminate the white marauders who disgrace their race by this cowardly murder of Negroes.”

Nathan Bedford Forrest memorial and grave in Memphis, Tennessee – Photo by DoxTxob (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

Forrest lived to regret his Klan involvement and would even become an advocate for the admission of blacks into law schools.

In 1875 Forrest was invited to speak before the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers Association, an organization of black Southerners seeking reconciliation between the two races. No one expected Forrest to attend, but he did.

He told the black audience,

“I came here with the jeers of some white people, who think that I am doing wrong. I believe that I can exert some influence, and do much to assist the people in strengthening fraternal relations, and shall do all in my power to bring about peace.”

In ending his speech, he expressed a sentiment perhaps gathered through the wisdom only time bestows,

“We have but one flag, one country; let us stand together. We may differ in color, but not in sentiment.”

He was widely condemned by the Southern press for the

“disgusting exhibition of himself at the negro [sic.] jamboree.”

Forrest would die in October of 1877.

So… do we take down his statue?

There are some incredibly stupid sculptures on display in the South.

The Boll Weevil Monument of Enterprise Alabama and the Mothman statue of Point Pleasant, West Virginia just to name two.

Idiotic as they are I don’t think they should be yanked off their pedestals.

According to the LA Times there are approximately 700 statues in the South commemorating the Civil War.

Do they all come down?

Flags are a different matter. Flags are the symbolic representation of a nation.

I don’t want the Crown of Castile flying over Florida, the French Fleur-de-Lis over New Orleans or the British Union Jack over Boston.

The Confederate flag therefore has as much legitimacy in being displayed over Richmond as the flag of Mexico does over Los Angeles.

But the statues….

I understand how black Americans and others can see some hidden threat or hushed taunt in having Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee peering down on them. But in pressing for their removal, they have allowed the knuckle draggers to usurp our history, and worse.

In fighting to destroy the liberalism they despise the Fascists always employ the very freedoms which the liberals have provided.

With the cry to remove the statues the Alt-right, Aryan Nation, White Supremacists and the rest of their peniculas clan have taken up the cry of “liberal censorship.” They are pounding us with the club that we handed them, and that is my primary concern for taking down the statues, I don’t want those dung beetles to be able to convince themselves that the rest of us are anything at all like them.

So what do I suggest?

One of the great truisms of our political system was spoken by Al Smith, the democratic Governor of New York for much of the 1920s. He said,

“The cure for the evils of democracy is more democracy.”

I say the cures for the evils of those statues are more statues.

My proposal is to reclaim our heritage from those seeking to use it as a means to divide us not by removing the statues, but by adding to them.

I would suggest on one side of Robert E. Lee be placed a statue honoring the most committed of all abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison who began publishing The Liberator in 1831 which would tirelessly voice its condemnation and spread anti-slavery sentiment across the nation.

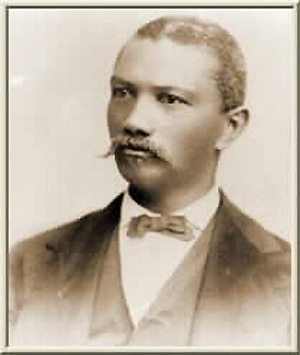

On the other side of Lee, I’d place a statue of Alexander Augusta. Born to free black parents in 1825, prior to the war, Augusta had been engaged in a battle of his own fighting against opposition to his entering medical school.

He had traveled to the gold fields of California to earn the funds necessary to pursue his goal of education and to pay for private instruction from a doctor. Finally, finding no college in this country that would accept him, Augusta traveled North to Canada where he was admitted to the University of Toronto, and from which he would received an M.B. in 1856.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Augusta wrote to President Abraham Lincoln offering his medical skills. In April of 1863 Augusta was commissioned a Major and appointed as a surgeon to the African- American troops.

Augusta would be the first of eight black medical officers to serve with the union army, saving countless lives by their presence.

In 1866 Augusta left the army as a lieutenant colonel, the highest ranking black officer in the country’s military.

Augusta would continue to fight racial discrimination in this country, and in 1868 was welcomed into Howard University to teach anatomy, becoming the first African American to teach medicine in this country and the first to be appointed to a college faculty.

At his death in 1890 he would be the first black officer to be buried in the Arlington National Cemetery.

Next to the statue of Jefferson Davis in New Orleans, I’d place one of William A. Jackson. Jackson was still held in slavery when the Civil War erupted, in service as coachman to his wealthy southern master. Jackson resolved to make a break for freedom at the first chance. Most slaves if they succeeded in reaching the north arrived with little more than the clothes on their backs. Jackson however realized he could take to the North a commodity that would be valued — information. So Jackson began to collect whatever he could pick up by spying on his master: Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy.

Dismissed as a “non-person,” as something “owned,” Davis would meet with his generals and openly discuss issues of vital importance while Jackson was present, with no more concern than if he were a chair or a hoe.

In 1861 Jackson “cut stick”” for the North and safely made his way the 90 miles to the Union line bringing with him information on supply shortages, as well as size and distribution of the Confederate forces.

Next to P. G. T. Beauregard I would erect a statue of Harriet Tubman. If Lee represents for a certain segment of our nation this iconic image of the Civil War, for many Tubman its mirror image.

Harriet Tubman Sculpture in Ypsilanti, Michigan by Jane DeDecker, Photo by Dwight Burdette (via Wikipedia)

A short, runaway slave, illiterate and given to seizures after having her skull cracked by a slave owner, she would prove to be a popular speaker on the evils of slavery, and would stealthily return to the Deep South more than a dozen times to lead other slaves to freedom in the North. For her courage and determination to see her people free Tubman would come to be admired by nearly all who met her. For her efforts in bringing other slaves out of bondage, William Lloyd Garrison, would nickname her “Moses.”

For most of the Civil War there was little certainty of what Robert E. Lee looked like. His youngest son would write,

“I believe there were none of the little things in life so irksome to him as having his picture taken in any way.”

Grant and Lee had ended the war, and Lincoln was assassinated. Famed photographer Mathew Brady was in Richmond photographing the ruins of the former Confederate Capital when he learned that Lee was nearby. Brady managed to have Lee agree to posed for six photos in uniform. After the session, Lee would put the uniform in a trunk and never touch it again.

In these photos you see a man a mere five years from death, who looks older than his 58 years. You see a man resigned but not defeated. You do not see humiliation but dignity; not a subjugated man, but a vanquished warrior.

To me, Lee has always represented the end of slavery in this country.

So beside Lee, I would put the beginning of that end.

Benjamin Lay was born in England in 1681 and would eventually adopt the Quaker faith and settle in Abington, Pennsylvania.

Lay was perhaps the first abolitionist and he possessed a striking sense of the theatrical that he would employ when making his points to others.

Once the whole town was in an upheaval when the young son of a Quaker slaveholder had disappeared. Panic consumed both the father and the township until it was learned that it was Lay who had kidnapped the man’s son so that he might learn how an African parent might feel when slavers took their children.

Lay, who was a strict vegetarian, would not wear, own or eat any product that resulted from an animal’s death or slave labor. He also wrote hundreds of pamphlets by hand, which he would pass out to all he came across, which condemned not only slavery but capital punishment and the brutality of prison.

In 1737 Lay’s All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates became his only published work when he gave it to a printer in need of work, a friend of his, the young Benjamin Franklin. It would be one of the most fervent polemics against slavery ever written in this country.

Lay would die in 1759 but his legacy was such that pictures of him could be found in the homes of early abolitionists for decades to come.

Those depictions of Lay were easily identified as he suffered from dwarfism and was a hunchback.

A small frame with a surfeit of righteousness.

So there my statues would stand Jefferson and Jackson, Beauregard and Tubman, Lee with Garrison, Augusta and Lay, rich in the fullness of history.

Our history.

♦ ♦ ♦

Thank You for Supporting the Voices of

The TVolution

Like us on Facebook and Please Subscribe

Tim E. | August 24, 2017

|

I recently saw a governor from one of the southern states speaking on this topic. according to him, it was all about ‘context.’ The statues could or should be mounted for viewing in an arena with other historical objects and materials. In other words, if the mounting of the statue weren’t as an homage to a most horrific time in the building of this country, but to explain the bones upon which our legacy sits, the statues would be viewed differently. He was, from the way I took it, speaking about educating the public as opposed to glorifying the dead individual. Somewhere in there… somewhere in what both Ernest and Steve espouse, lies a solution.

We cannot and should not forget where we came from, because it will always be a part of who we are. Should we hide the statues away? Will that take away some power they hold over those that worship at their feet? Or will it, on some level, sear the seed of hate, to which they cling, so deep, there can never be a chance to convene together for calm discussion?

Or are we just giving up now….?

I once thought there was a chance for this country to be as prejudice-free as any country could ever be, Recently, I’ve begun to believe that no one has the answer anymore. I want to be wrong. am I?

Steve Schlich | August 23, 2017

|

Thanks, Ernest, for this strong argument. IMO the problem is that the existence of so *many* statues argues for them representing political and social statements–of white superiority–rather than honoring a man.

I think their intent is to prevent people from acknowledging the basic fact of the Confederacy, that it was not the fabled “Lost Cause” but a traitorous event. I think that the statues do not fulfill your honorable purpose of memory but attempt to revise memory. How we solve that one? I don’t know. More honest education?