Antony and Cleopatra has it all — magnificent history, towering characters, stunning pageantry and poetry of the highest order — yet it is one of Shakespeare’s least produced plays

The difficulty with the play is that its trinity of major characters are among the most arduous and obfuscated the Bard has ever penned. Octavius, Antony and Cleopatra are not the sorts we’d like to have as house guests. Octavius (the future Augustus for I, Claudius fans) is not without a sense of nobility, but has all the warmth of a glacier, while Antony and Cleopatra are vain and willful and so annoying that today they would likely have their own reality TV shows.

The virtues of the play’s two lovers while not immediately apparent, are revealed slowly, like the peeling of an onion, which is part of the play’s difficulty as well as a display of the playwright’s mastery of his craft.

For here Shakespeare gives us something altogether different; not a pair of lovers who are destroyed by their challenge to or defiance of the world about them, but two lovers who destroy themselves and their worlds, by the love they share.

Cleopatra and Antony serve as negative and positive ions to each other; her energy is expressed in love and power while he is the reverse charge, a creature of power and love.

Their love doesn’t enrich the world, it feeds on it. And them.

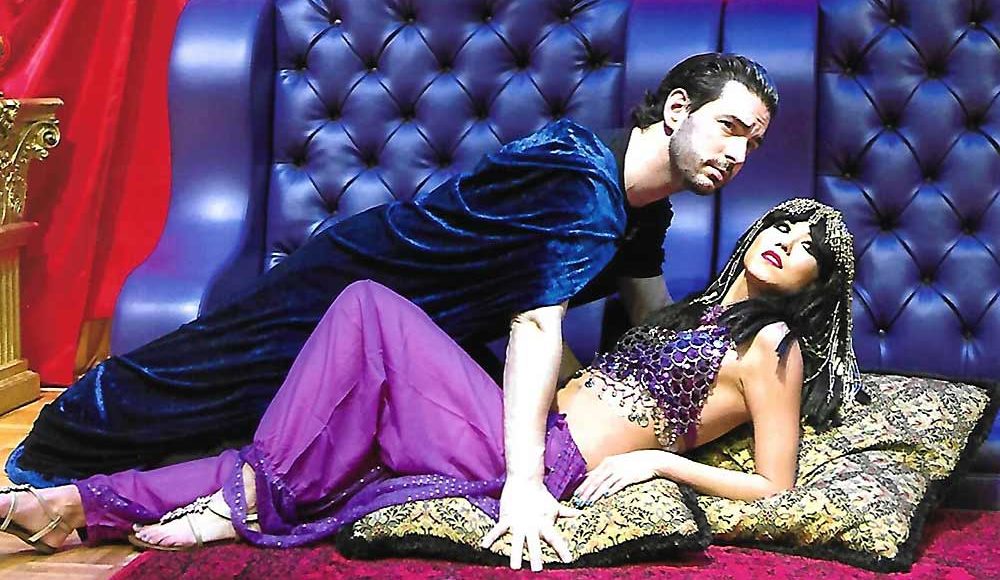

Antonio Roccucci, Danny Siegel in ‘Antony & Cleopatra’ (Photo by Mathew Caine / Studio Digitrope – Courtesy of Jamaica Moon Productions and GGC Players)

To rule the world, Shakespeare seems to be telling us, demands the death of passion. And nowhere is this better conveyed than when Thyreus, in the service of Octavius, tries to break apart the alliance of lovers.

Thyreus, in perhaps the most revealing dialogue of the play, delivers to the Egyptian queen Octavius’ message –

– it would warm his spirits

To hear from me you had left Anthony

And put yourself under his shroud,

The universal landlord.

As always with Shakespeare, his word choice is staggering in its preciseness.

To possess this woman of fire

– “it would warm his spirits.”

He wishes her to leave Antony whose vaulting ambitions will quake the empire for him a “universal landlord.”

Antony cannot resist her arms and bed, but Octavius offers to put her “under his shroud.”

The word is overburdened with foreshadowing and irony.

Nobody understands the Bible better than a non-believer; Shakespeare shows this, throughout his plays in his reflecting and echoing of scripture. One could make an argument that his greater works are rooted in a single passage.

For Anthony and Cleopatra, Matthew 16:26 seems a perfect fit.

“For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”

The beginning of the verse, addresses Cleopatra’s dilemma throughout the drama, knowing that even if she gains the whole world with the “universal landlord” that without Anthony what waits is the “shroud.”

Anthony’s dilemma is found in the lesser known second half of the verse:

“Or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?”

In Anthony’s case, it is the Empire of Rome for Cleopatra’s arms.

Many happy endings are found in Shakespeare where love plays a part. But where love is two near the maelstrom of power – Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Othello, Henry V – the evening is certain to close on a corpse-strewn stage.

For Shakespeare, love is always crouched in terms of conflict and combat. In Anthony and Cleopatra, the drama is set on a rising tier of battlefields.

The idea of setting contemporary music to Shakespeare is nothing new, and works well with his comedies most of which are saturated with music.

Antony and Cleopatra is among Shakespeare’s least musical works and is….well, not a side-splitter.

In Antony and Cleopatra — The Musical, Director/Executive Producer Gloria Gifford offers little originality and brings no insight to her effort to fuse contemporary music with Shakespeare’s poetry, and while she announces her intention was to make the work more accessible to audiences, the opposite result was the case.

There is much that hinders the evening. Not the least of which is Gifford’s putting 35 actors on stage that neither she nor the venue can manage.

One must assume that the only reason for this tidal wave of thespians washing over the stage is that they represent all those enrolled in the classes Gifford offers.

This as the guiding rationale in casting does not bode well, and hampers any fluidness on stage and eliminates any possibility of gracefulness of movement. Instead what you have are long-ragged lines of actors continuously marching on and off stage as if in search of auditions for a sequel to The Human Centipede.

For the most part the choice of songs seems plucked from a collection of Golden Oldies, without any great consideration put into their selection.

But a lack of commitment to the conceit was the most damaging element of the production.

During the songs involving the bulk of the cast a few sway, a few half-heartedly snap… then they all go marching off.

There is more marching in this show than you’ll find in the combined Super Bowl halftimes of the last decade.

In performing the musical numbers some of the actors would sing along until notes reached too high or low and then they would fall silent. When it is the voice of Judy Garland that they are competing against this is not a bad idea.

When the actors lip sync to the songs it is usually without much commitment or success.

Hailé D’Alan (front), Nancy Vivar, Joey Marie, Yvette DeVito (Photo by Mathew Caine / Studio Digitrope – Courtesy of Jamaica Moon Productions and GGC Players)

There were some exceptions, Antonio Roccucci, who boasts quite a pair of pipes, managed to pull off his duet with James Ingram’s One Hundred Ways, and later in the junction of “War” with “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction” the cast offered up one of the few moments that stirred the dust off that had collected on the audience.

Perhaps if Gifford had the chops to introduce the edginess of Dennis Potter’s Pennies from Heaven, the concept might have worked, but as the overall cast seemed unable to rise to the demands of Shakespeare it’s unlikely they would have been any more successful in a Potter fusion.

I know the work of only one actor, Hailé D’Alan, who did an excellent job at the Odyssey in the title role of Steven Berkoff The Hairy Ape. Here, as the noble Enobarbus, he is less successful.

There could have been more talent on the stage than appearances would lead one to believe, but if there were it was crushed between the rock and the hard place of Gifford’s direction and lackluster handling of her concept.

Also the decision not to attach characters names to the performers in the program doesn’t make the job of a reviewer any easier, especially with a cast of nearly two score.

The play of Antony and Cleopatra is a challenging undertaking. Not the least for the fact that the two main characters only find their true nobility in the very last scenes of the play.

In this fashion Cleopatra is not unlike Othello and Antony another Desdemona in that the death of both are caused by the one they love and that neither die with any recriminations on their lips for their imperfect lovers.

It is only when their power, title, rank and authority has been stripped from them and they are left with nothing save their love that Antony and Cleopatra obtain the level of Shakespeare’s greatest creations – Lear, Hamlet, Juliet.

In their last moments of the play Shakespeare reveals what is to be admired and pitied in this pair of lovers who did the work of the “stars” in the crossing of their fates.

In the play it is a beautiful moment.

In Gloria Gifford’s Antony and Cleopatra – The Musical, you’re just glad it’s over.

♦ ♦ ♦

Antony and Cleopatra: the Musical ran thruout December at The Gray Studios in North Hollywood

Thank you for Supporting the Voices of The TVolution

Like us on Facebook and Stay Updated,

Please Subscribe in the Newsletter Box Left Hand Side

NOTE FEATURED IMAGE: Danny Siegel and Tejah Signori (Photo by Mathew Caine / Studio Digitrope – Courtesy of Jamaica Moon Productions and GGC Players)