Now I’ve seen some truly remarkable acting at this year’s Fringe, but here are two amazing ensembles that stand out head over shoulders above most of the others….

Now I’ve seen some truly remarkable acting at this year’s Fringe, but here are two amazing ensembles that stand out head over shoulders above most of the others….

NEVA

On a stage, three actors await their director in a cold gloomy rehearsal room in the Russian city of St. Petersburg. The only set: a chair within a circle of torn books and shredded pages enclosing them like some necromancer’s ritual ring of protection. And they are in need of protection, though they don’t quite realize that at first, on this date of January 9, 1905.

Outside they hear shooting, but they are more concerned with the upcoming production they are performing in, unsure what roles they will play.

The shooting outside, that they hear, will be remembered by history as “Bloody Sunday.”

It was the day Father Georgy Gapon leads a huge mob of unarmed demonstrators to the Winter Palace. Their intention was to present Tsar Nicholas II with a petition stating their grievances while asserting their devotion to the Tsar.

As they neared the Palace, the Imperial Guard fired on them killing hundreds. It would later be learned that Nicholas wasn’t even in the palace at the time. The massacre on Bloody Sunday would be one of the key events leading up to the Russian Revolution of 1917.

But the actors are oblivious to the history in the making outside the theatre walls.

Olga Knipper (Claudia de Vasco) is the widow of playwright Anton Chekhov, and that the play opens with her toiling desperately to recite the final monologue of The Cherry Orchard, announces to the audience not to trust the line between reality and illusion.

Olga along with the two other actors, (the toadying Aleko (Daniel Jimenez), and the submissive Masha (Anna Safar)) while away their time in gossiping about their fellow actors, and recreating with Olga’s prompting scenes from Chekhov life and his death. They flirt, they debate the nature of the actor – all the while ignoring the inferno raging outside their sanctuary of illusions.

Playwright Guillermo Calderón is a Chilean playwright living in New York, and Neva is his first play.

The play is rich with the delusions people place between themselves and the brutality of history, which resonates with the history of Chile whose population suffered a sixteen-year right-wing dictatorship, under Augusto Pinochet; surviving by closing its eyes to the worst abuses of said government.

Calderón’s play (translated by Andrea Thome) is a rich, constantly perplexing but ultimately intriguing diatribe on the individual’s inability to take responsibility for their history, preferring the safety of playing roles rather than being participants in the making of their own fates.

The language is rich and full, as one often finds when the writer is discovering English anew.

Diana Wyenn fills the tight arena of the stage superbly with the preponderancy that is Calderón’s play, never allowing the language to overwhelm the immediacy of the moment or bog down the actors. Wyenn is well aided in this by Joey Guthman’s beautifully realized scenic and light design.

It is, though, the actors, representing the microcosms of life, art, illusion and reality with which Calderón envelopes the audience.

The ensemble is orchestrated with a deftness that delivers the play from any number of pitfalls that it could have fallen into. De Vasco dominates the play early on with Jimenez, but it is the mousey Masha who finally joins the storm of history swirling about the theatre and giving voice to the tempest set to blow all their world away.

The play itself is a fascinating work, but it is the performances that will take your breath away till next spring.

The play itself is a fascinating work, but it is the performances that will take your breath away till next spring.

Find out more about this company and this production HERE.

Also, please subscribe above. The TVolution will alert you to any extensions.

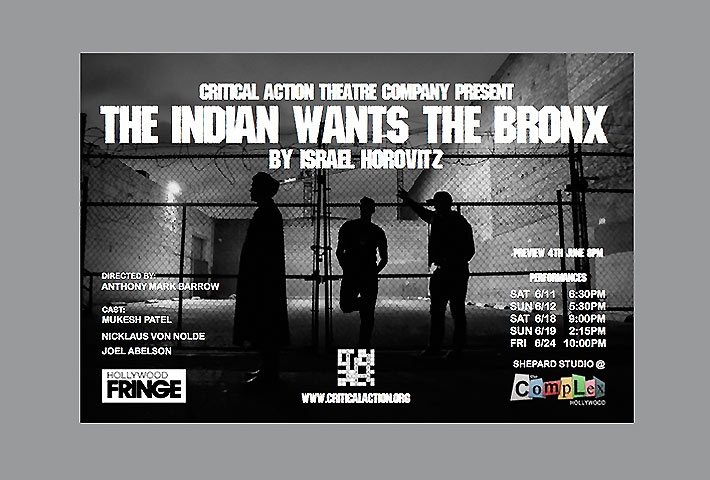

THE INDIAN WANTS THE BRONX

Israel Horowitz has never captured the recognition of his contemporaries Sam Shepard or Terrence McNally. This can partially be attributed to his long absences from the American stage, living and working in France. He has written screenplays but for films of middling success and always separated by long periods in between: The Strawberry Statement (1970), Author! Author! (1982), Sunshine (1999).

He is best known for his theatre work from the late ‘60s and early ‘70s of which the one act The Indian Wants the Bronx is, perhaps, his best known.

He originally wrote this study of urban violence for a then unknown actor by the name of Al Pacino.

The play opened in 1968 staring Pacino and John Cazale both of whom won Obies for their acting, as Horowitz did for the play.

Like all of Horowitz’s early works, the play is stark and simple in its plotting; two street toughs, Joey and Murphy happen upon a lost Indian tourist and brutalize him.

Horowitz had a long association with Samuel Beckett and, at times, his plays approach the minimalism of the Irish playwright’s work with however the absurdity of life expressed in mindless, inexplicable violence.

The loud, boisterous Murphy (Joel Abelson) and his faithful flunky Joey (Nicklaus Van Nolde) are out and about rough housing in a rundown portion of the Bronx when they come upon Gupta (Mukesh Patel); an Indian tourist who has become separated from his son on his first day in New York.

Mocking his appearance and his “foreignness” Gupta becomes the object of a vicious contest of one-upmanship between Murphy and Joey as they torment the confused Gupta who struggles to make himself understood despite his limited English.

The inability to communicate is a key feature in Horowitz’s plays. Not merely Gupta’s inability to connect to his two tormentors, but Joey and

Murphy’s inability to communicate to each other and themselves, except in terms of physical abuse.

Horowitz seems to be putting forth, that primitive language is the precursor to primitive acts. In which case, the Critical Action Theatre Company and director Anthony Mark Barrow recognized how the play spoke clearly to our current social environment of xenophobic fear and violence.

Director Barrow manages to avoid the inherent “Bouncing Betty” of the piece, the near non stop Alpha dog aggression Joey and Murphy display towards each other, Gupta and even their probation officer in a distant high rise. Unchecked, the relentless tide of testosterone can be damning, but Barrow succeeds in modulating it, and laying in distinctions between the specific head-butting.

As Murphy, Abelson is a towering presence who easily dominates both Joey and the hapless Gupta but manages to convey the desperation beneath his bravado and the uncertainty that shadows his strut.

Van Nolde plays his envy, admiration and hatred of Murphy in well mixed doses. He is the more compassionate of the two, but knows that showing that compassion would have him dismissed as a “homo.”

Left alone with Gupta, Horowitz again shows through Joey’s fumbling efforts that it is our inability to communicate with each other and ourselves that is our undoing.

Both characters of Joey and Murphy are younger in the play than here. In the original production, Pacino and Cazale were 26 but their slight frames made them look younger, filling the concept then held as the source of violence in the inner cities: juvenile delinquents.

Both Abelson and Van Nolde appear in their mid-thirties, and this seems to work. Now-a-day’s our boogieman is middle-aged.

Abelson and Van Nolde are demonic dervishes of violence that sweep the stage with hurricane-like force. I could sense that the audience was hoping for some intervention, some deus ex machina to arrive and deliver the tormented Gupta.

But such devices don’t exist in Horowitz’s universe. Maybe not in ours either for all our prayers and all our liberal optimism.

As Gupta, Mukesh Patel has the challenge of a role consisting of nearly all unspoken subtext, and he must progress on an arc of extreme emotions from perplexity to fear to indignation to desperation to rage – all with minimal dialogue.

But through it all he must maintain his humanity, a humanity that is alien to his tormentors which Patel does with perfect precision. And so when he stood before the audience for the play’s final moment you could hear sobbing in the theater.

Yes, sobbing for what he had suffered, but also sobbing at what we are capable of.

There is a saying about the suffering we can inflict on our kind, “Man is to man a wolf.” The use of the large canine meant to convey the viciousness we can display on our own species.

But we all know that saying is incorrect.

It should be, “Man is to man a man.”

Be forewarned, in seeing this play you are placing yourself in the path of an emotional juggernaut, fueled by three amazing actors and it will crush you down with despair.

But perhaps that’s what we need as a wake up call for this nation and our people, a wake up call to show us in harshest terms how little we’ve evolved.

Playing at the Complex Theatre in Hollywood, Friday June 24th at 10pm marks the final Fringe Performance

Playing at the Complex Theatre in Hollywood, Friday June 24th at 10pm marks the final Fringe Performance

Learn more about the show and any extensions HERE.

Be sure to subscribe, above, and keep informed about the arts in Los Angeles and more.

Two days of plays remain to see at Hollywood Fringe 2016. Check this space.