The intended purpose of this monthly column is to bring to the attention of cinema junkies those odd and typically genre defying films which may have slipped, justifiably or not, beneath the radar of even the most diehard film aficionados. For the offerings I shall be presenting here, I will roam the vast ranks of recent releases as well as plum the dust bins of the past, in the hopes of calling the reader’s attention to some true gems, or at least some highly polished coprolite, that will amuse, delight or outright bewilder even the most blasé student of the diminutive celluloid square.

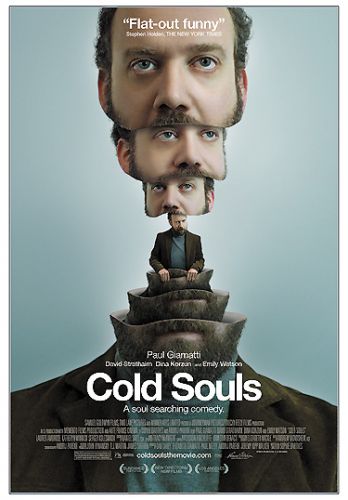

COLD SOULS (2009)

I am always slacked jawed by films that so avoid classification that it drives some clueless marketing director, not knowing at all what he has, to try selling it as what he hasn’t. Two good examples of this maneuver are the films Mr. Jones (1993) a grueling examination of the trials facing manic depressive conditions, starring Richard Gere, and Hard Core Logo (1996), a bleak study of how the very qualities that account for the artistic drive also serve to make realizing any satisfaction in the pursuit of the creative ideal impossible. In what can only be regarded as a cynical tactic to maximize opening box office revenues, both were sold as comedies.

In undertaking this for Mr. Jones, the task was not overly demanding, with TV promos and theatrical trailers consisting of clips where Gere’s character was at the apex of his psychological cycle allowing for an easy spin on his character as a “wild and wacky guy!”

In the case of Hard Core Logo, which had a limited theatrical release, it was a question of grooming the reviews judicially. Not a troublesome operation to pull off with the three gazillion web sites operating as armchair Eberts: Film Junk, TasteKid, Blog de Cine, ScreenCrave to name a few; after which it’s just a matter of finding the right critic off his meds.

Hard Core Logo, which ends with a nihilistically tight close up of one character’s on camera suicide was promoted on the cover blurbs as “Punk Rock’s Spinal Tap.”

Cold Souls is condemned to the same fate with quotes from the New York Times and Rolling Stone describing it as “Flat out funny” and “You’ll laugh till it hurts.” My quick scan of both supposed sources could find neither quote. Sophie Barthes, who’s short Happiness was widely well received, is both writer and director for Cold Souls, her first full length feature.

On its release in 2009 it came in for a goodly portion of criticism centering on perceived similarities to Charlie Kaufman’s Being John Malkovich (1999) of which there are some. In both Kaufman’s and Barthes’ work, the central characters are ostensibly portraying themselves, but the same device is used in Free Enterprise (1999), the film that allowed William Shatner to reinvent himself with such great success. They do share a similarity of tone, but I would distinguish the earlier with the label “fantasy-fable,” while Barthes’ is a more Orwellian “sci-fi fanciful”; the idea for which she claims came to her in a dream.

Otherwise I saw little else the two works shared, Being John Malkovich does provide an adequate weather vane, in that if you found the Kaufman’s film entertaining then you’ll likely appreciate Barthes’ variation on the theme.

We open on an actor, Paul Giamatti (played brilliantly by… Paul Giamatti), struggling with the titular role in a Broadway revival of Chekov’s Uncle Vanya. With the opening looming close at hand Giamatti, racked by angst and self-doubt, sees disaster ahead for the show and himself. An article in the New Yorker seems to hold the remedy for his creative constipation. A high tech service corporation, obtusely named Soul Storage Company, offers an unusual service; providing storage for its clients’ souls.

Skeptical at first Giamatti sets up an appointment and after assurances by the highly reassuring Dr. Flintstein (David Strathairn), he opts to undergo the procedure. His soul is harvested out of him via a very imposing looking device, and much to Giamatti’s annoyance his soul resembles in size and shape a chickpea.

At first Giamatti feels liberated, as if the removal was a psychic enema, and rehearsals move along smoothly. After opening night Giamatti returns to reclaim his soul, having realized that burdensome as it may be, it is also the font of his talent. But arriving at the storage facility Giamatti discovers his soul is gone. Stolen! We come to learn that he has fallen victim to an international black-market of stolen and resold souls centered in Russia. And though good Dr. Flintstein offers Giamatti his choice of “in house” souls, which have come into the company’s possession due to missed monthly rent payments, Giamatti is determined to recover his own. Eventually he locates the soul smuggling mule Nina, (Dina Korzun) responsible for pilfering his soul and finds that it was stolen for a Russian mobster’s soap opera star girlfriend (Katheryn Winnick) who had thought she was getting the soul of Al Pacino. So, with no other choice, Giamatti sets off to search for his soul in Mother Russia.

Though the film’s central concept treads close to the absurd, Barthes never allows the film to stray into the farcical or even the comical and her tongue never comes into the same time zone as her cheek. The worlds of her film are either the claustrophobic whirlwind that is Manhattan or a grimy and gray St. Petersburg strangled in winter’s icy grip with the unyieldingly bleak look of the two locations captured strikingly by Barthes Cinematographer and husband Andrij Parekh.

If there is a prevailing flaw in the film, it is the sense that Barthes has fashioned a feature length work physically but has installed it with the interior life fit for a far shorter work. But while one will probably not experience complete satisfaction at the end of Cold Souls, it is unlikely that the journey offered by this surreal cautionary fable will be a disappointment to those who travel with it.

The moral lesson Barthes appears to be putting forth here is one learned from the clam and the sand grain. For the clam, the unnatural intrusion of a sand grain into its shell is soon a source of pain and discomfort. To ease this irritation, the clam produces a secretion that coats over the grain and hardens, the process by which pearls come into existence.

So an object of beauty has its beginning in suffering.

Within the human shell, pain can be in grains of memories, and creativity may be said to be the pearl we produce. Barthes exploits events, which are no less tragic for being placed at the peripheral of her film, to be a caution for us: that if we liberate ourselves from the suffering of our souls, we may find a calm harbor within our breasts. But to only sail smooth seas is to never know the poetry in the storm.

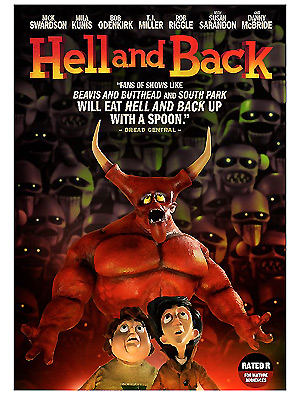

HELL AND BACK (2015)

Now just the collection of talent involved in the making of this stop action animation musical re-rendering of the Orpheus myth as a goofy buddy flick is worth standing back and taking notice of:

T.J. Miller, a recognizable face from HBO’s Silicon Valley and now Deadpool (2016) –

Bob Odenkirk earned laurels from Breaking Bad and has gone on to earn more on Better Call Saul –

The lovely Mila Kunis gives voice to the long suffering Meg on Family Guy –

Danny McBride from Despicable Me and Up in the Air – and now Vice Principles

Kerri Kenney, beloved by Reno 911 fans as nerd-goddess Deputy Trudy Wiegel –

Lance Bass of former boy band fame with the group NSYNC –

H. Jon Benjamin the voice of incessantly inebriated super spy Archer –

With Susan Sarandon, Michael Peña, Greg Proops –

Co-directed by Tom Gianas, who cut his teeth writing and directing for Saturday Night Live back in the day,

and Ross Shuman of Robot Chicken: Star Wars and Moral Orel fame.

With that list in mind two questions immediately spring to mind – how much fun was it to be in the studio with this one, and why isn’t it just an utterly awesome wet yourself laughing film?

The narrative seems to be in place:

The narrative seems to be in place:

Remy (Nick Swardson), a slacker version of Horatio Alger’s Ragged Dick, struggles to keep the threadbare, old pier amusement park he runs from sinking beneath all the red of his business ledgers. He receives little help in this from his childhood friends; the plump and sincere Augie (T.J. Miller), and the cheeky hemp-loving scalawag Curt (Rob Riggle).

Remy thinks he’s hit on a possible way to avoid foreclosure when the pier’s wizen sexpot fortune-teller Madame Zonar (Kerri Kenney), shows him this ancient satanic text on the cover of which the image of Satan is actually crying.

Heck! Folks lined up for days to see a tortilla with Jesus’ profile burnt on it, so why not a book cover with a blubbering Beelzebub. But before Remy can think of the proper method of exploiting this asset, to make a long story short, Curt and Augie accidently send him to hell.

Oops.

Braving the Underworld to rescue him, Curt and Augie meet that hipster douche of Hades—Satan, (a very amusing Bob Odenkirk), Barb the MILF angel (Sarandon), a plucky Succubus (Kunis), and an oak (H. Jon Benjamin) modeled along the lines of Dante’s trees, who makes no secret of his fondness for little boys.

From the start of the film, you can’t help wondering why you aren’t laughing more, and it feels like you’re watching a Three Stooges short where Larry, Moe and Curly Joe are all heavily sedated.

But by sheer tenacity Hell and Back starts to win you over.

A pole dancing angel with a rump to eat off of, a romantic ballad sung by Orpheus (McBride) about ass raping oak trees and a duet between him and the angel Barb where they lament in song:

They all said that our love stood not a chance,

Because our hearts couldn’t keep it in their pants –

I don’t know about you, but they had me at the “pole.”

Eventually you are won over by the total dopiness of it all, and some first rate animation work.

When the fat lady finally screams in eternal damnation and the brimstone settles, the worst that can be said of Hell and Back is that it’s essentially Robot Chicken-lite.

Which when you think about it, isn’t all that bad.