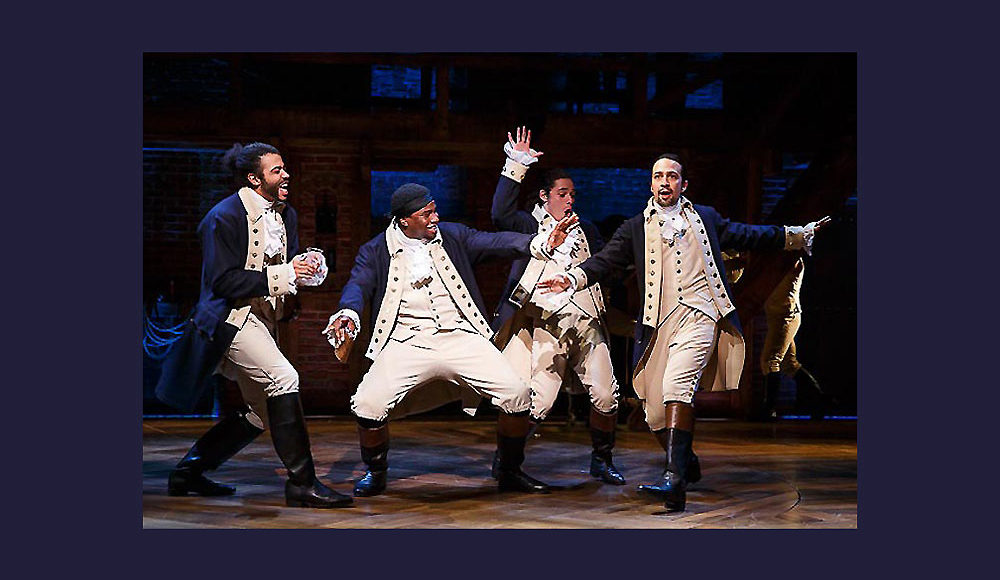

In Part I, we celebrated two dazzling effects of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s landmark musical Hamilton: with his theatrical retelling of our founding era, he has managed to make American history 1) hot-blooded and 2) cool – at the same time!

A third jewel in Mr. Miranda’s crown of achievements is this: he’s brought Broadway back into the mainstream.

I know theatre purists – and many a New Yorker – will howl at this, but it’s true: Broadway theatre has become an elitist art form, limited in its audience by both geography and astronomical ticket prices. Mainstream culture is dominated by the wide global reach of television and movies.

Broadway is elitist in the same way ‘artisanal’ products are: it’s personally made in small batches, and available for distribution only in a limited area. The Broadway musical simply has not held a prominent position in the national entertainment scene for a long while.

When I was coming of age in Detroit, Broadway did seem to hold a center spot in American popular culture. Recordings from many a musical regularly appeared on the charts; covers abounded, and original cast albums frequently topped the charts. (In fact, Louis Armstrong’s cover version of “Hello, Dolly” bounced The Beatles out of the #1 spot on the Billboard singles charts in 1964.) The Ed Sullivan Show frequently treated us to numbers from current or upcoming shows, and hugely popular magazines brought us the backstage stories of the stars. And then there were the cast albums.

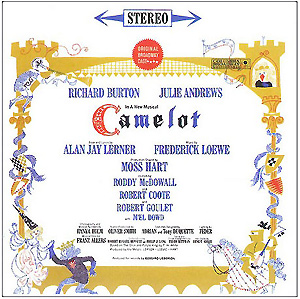

Mr. Miranda refers to himself as a cast-album kid in a number of interviews I have seen and read. That phrase could describe me as well. In fact, the closest experience I’d had to that first hearing of the cast album of Hamilton was listening to the original cast album of Camelot, an album which had magically appeared near our living room stereo when I returned from school one afternoon.

Of course, I had seen Richard Burton and Julie Andrews on the Sullivan show by then, and I knew the basic story of Camelot and the tales of King Arthur. But listening to the whole story of promise, romance, betrayal, jealousy and heartbreak left me in tears that first afternoon – and in almost every listening thereafter. The experience with the story of Alexander Hamilton has been remarkably similar: knowing the broad outlines of the story, and then being drawn in by the humanity, the triumphs and the sorrows: repeated listening sessions of Hamilton have had the same effect on me as Camelot had on that eighth grader all those years ago.

Of course, I had seen Richard Burton and Julie Andrews on the Sullivan show by then, and I knew the basic story of Camelot and the tales of King Arthur. But listening to the whole story of promise, romance, betrayal, jealousy and heartbreak left me in tears that first afternoon – and in almost every listening thereafter. The experience with the story of Alexander Hamilton has been remarkably similar: knowing the broad outlines of the story, and then being drawn in by the humanity, the triumphs and the sorrows: repeated listening sessions of Hamilton have had the same effect on me as Camelot had on that eighth grader all those years ago.

The original cast album of Camelot spent over 200 weeks on the Billboard charts, and was the top-selling album in the country for 60 of those weeks. That’s how mainstream Broadway used to be.

While we don’t have the likes of Ed Sullivan anymore, we do have Twitter and Facebook and YouTube, and that’s where I’ve seen Mr. Miranda nudge Broadway back into the mainstream. I started following him on Twitter a few years ago, and watched as his number of followers exploded not long after the off-Broadway debut of Hamilton early in 2015. Have I mentioned yet that the original cast album has topped the Rap charts, made the Top Ten album charts and had the highest debut of any original cast album in 50 years? Well, it did – all of those things.

Mainstreaming also means broadening the audience, and that’s something the folks behind Hamilton have done brilliantly. When the show moved from the Public Theatre to Broadway, they introduced the genius concept of a #HamforHam – a lottery at each performance that entitles several winners to two tickets in the front row for $10 each. In gratitude for the amazing turnout of people willing to stand in the heat, rain, cold, whatever, to support live theatre, Mr. Miranda started casual #HamforHam shows: five-minute sidewalk performances by Broadway veterans mixed with pop stars mixed with members of the company. The crowds that gathered soon became somewhat of a headache for the NYPD, I gather, but the energy generated became somewhat of a tonic for Broadway.

Lest you think that was just a bunch of folks enjoying ‘Summer in the City’ here’s a shot from January 2nd of this year when it was considerably chillier hanging out on 46th Street for a while.

I haven’t read about crowds like this in the theatre district since I was a theatre history student and read about the Macbeth riots in Astor Place in 1849. (Look it up; crowds fighting over competing Macbeths – honest.)

Alas, the live #HamforHam shows have been retired until further notice, although occasional digital versions may appear. As the show’s producer, Jeffrey Seller, said at the end of August, “It’s like we’re going back to school: We have so many activities going on, we’re concerned about traffic, and we’re concerned about being good citizens. It’s time to pause.” (Fortunately, the #HamforHam ticket lottery continues – and it, too, has gone digital.)

So that’s Mr. Miranda’s third jewel – mainstreaming Broadway for a new generation.

I’m guessing he will add a fourth with his upcoming collaborations with Disney. But first, a little diversion to discuss Disney’s place in the canon of the American musical.

I’ve had two occasions to study the history of the American musical. The first was when I was writing my college dissertation on the history of the American musical theatre. The second was when I was writing my novel Finales and Overtures in the mid-90s. In order to write bios for all my characters, all working on bringing a new musical into New York, I had to revisit the Broadway cast albums of the prior 50 years so I’d have an idea of their influences and favorites – their own particular Broadway histories. I luxuriated in listening again to all the Rodgers & Hammerstein shows; I gained new respect for Lerner & Loewe as I studied their songs and absorbed their adherence to the classic structure of musicals; I was newly astonished by the solo work of Frank Loesser and Meredith Willson and mourned the passing of Jonathan Larson.

I also came to appreciate what a unique role Disney played – from the mid-80s on – in preserving the classic American musical form during a time when the European style of musical theatre dominated Broadway. Howard Ashman and Alan Mencken’s work in The Little Mermaid and then in Beauty and the Beast and then Mencken with Stephen Schwartz in the under-appreciated Pocahontas all followed the classic American form, much as Lerner and Lowe works had. A few of the Disney animated films have already made the transition to the Broadway stage, and I’m sure others will follow.

I also came to appreciate what a unique role Disney played – from the mid-80s on – in preserving the classic American musical form during a time when the European style of musical theatre dominated Broadway. Howard Ashman and Alan Mencken’s work in The Little Mermaid and then in Beauty and the Beast and then Mencken with Stephen Schwartz in the under-appreciated Pocahontas all followed the classic American form, much as Lerner and Lowe works had. A few of the Disney animated films have already made the transition to the Broadway stage, and I’m sure others will follow.

Mr. Miranda was obviously influenced by such European musicals as Les Misérables, and Phantom of the Opera, but he has thoroughly Americanized that style with Hamilton. With his announced contribution to Disney’s upcoming Moana, an adaptation of the origin stories of the Maori people of the South Pacific, he adds another line of continuity to American musical history. Given that he is such a student of musical theatre, I’m sure the rounding of this circle in so many ways is as much of a joy to Mr. Miranda as it is to his admirers.

His collaboration with Disney will continue with the recently announced Mary Poppins Returns, where Mr. Miranda will be starring with Emily Blunt and Meryl Streep. Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman, the musical team behind Hairspray, are creating an original musical score for the sequel, but it doesn’t take too much of a leap to imagine that the Tony and Grammy winning composer and lyricist of Hamilton may contribute a tune or two.

Here’s wishing enormous success to Lin-Manuel Miranda, both with Moana and with Mary Poppins Returns. But I hope that, even with great successes in the traditionally mainstream media, he will return to Broadway – soon. There is room for several more jewels in that crown of achievements.

* * *

For Why Hamilton is Historic Part I Click HERE.