by Ernest Kearney — It would be difficult to find two more dissimilar figures than the British lay theologian, academic and novelist Clive Staples Lewis and Sigmund Freud the secular Jew and father of psychoanalysis, whose theories of symptom formation, the unconscious, and of the magnitude of repression layered with the interaction of the id, ego and super-ego all but obliterate the notion of free will in man.

Freud, like many of the cultural elite of Europe’s Jews, was late in recognizing the threat posed to them by the rise to power of Nazi Germany. Freud even saw the early burning of his books, along with the banned works of Albert Einstein, Friedrich Engels, Franz Kafka, Karl Marx, Erich Maria Remarque, Ernest Hemingway, Helen Keller, Joseph Conrad, D.H. Lawrence, H.G. Wells, James Joyce and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, as a sign of progress.

“In the Middle Ages they would have burned me,” he quipped. “Now, they are content with burning my books.”

Freud’s intellect blinded him to the barbarism of Hitlerism. Even an early offer of passage to America he declined, expressing his disdain for this nation in blunt terms, “America is gigantic, but a gigantic mistake.”

When Vienna came under Germany’s control, Freud still hesitated to seek a safe haven away from the ever-present danger of the Nazis now surrounding him. Only after the Nazis had confiscated his savings and property, closed down his publishing company and arrested his daughter Anna did Freud finally agree to seek asylum. Upon paying the heavy “flight tax” imposed on him with the financial help of Princess Marie Bonaparte, the great-grandniece of Emperor Napoleon I, Freud and his immediate family were given visas and allowed to leave for London in June of 1938.

For Freud’s elderly sisters, his reluctance to accept the realities of the danger, he and his coreligionists faced, proved deadly with all four dying in Hitler’s death camps.

Freud settled in the London suburb of Hampstead at 20 Maresfield Gardens. a stately Queen Anne Style manor. Freud called the number 20 to his daughter Anna, “Our last address on this planet.”

He was right, he died a year after arriving there. Anna would remain in the house till her death in 1982.

During his brief time living there, Freud continued writing on his final works, Moses and Monotheism and An Outline of Psychoanalysis, even seeing a few patients; all the while suffering from the increasing torment of the cancer in his jaw which, following 15 operations, had been declared terminal.

This period also saw Freud visited by such callers as Virginia Woolf, Salvador Dalí, Ernest Jones and H. G. Wells. Among those notable figures there was also a young Oxford professor recorded as coming to pay his respect whose identity is unknown.

That this young professor could have been C.S. Lewis has given playwright Mark St. Germain the premise for Freud’s Last Session.

This is the second production of St. Germain’s play in L.A.: the first being a mounting at the Broad Theatre in 2013 and starred Judd Hirsch— of Taxi fame— as Freud and Canadian actor Tom Cavanagh— whose introduction to American audiences was on the series Ed— playing opposite Hirsch as Lewis.

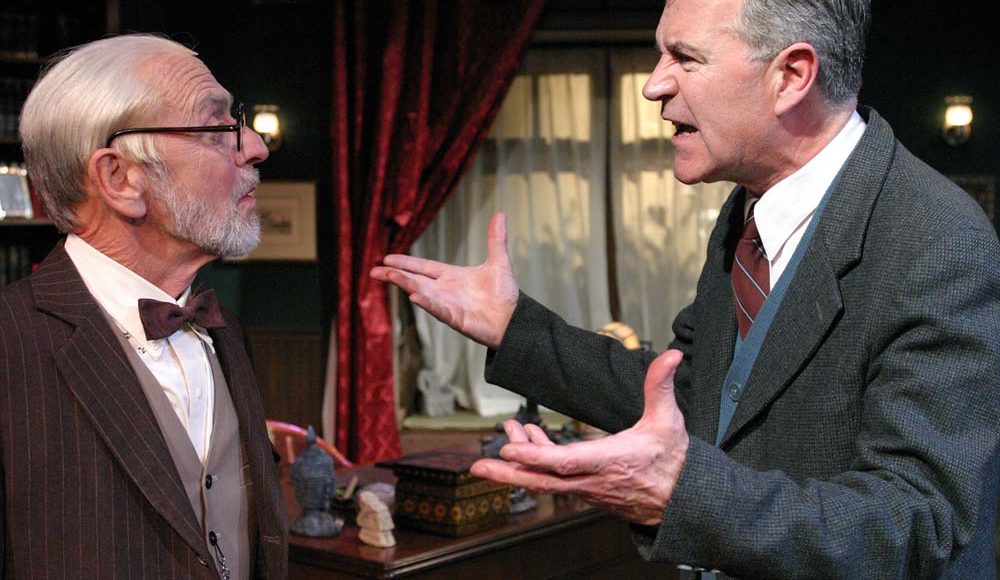

The actors called on to fill the roles in this new staging at the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble, Martin Rayner as Freud to Martyn Stanbridge’s Lewis, don’t come encumbered by that heavy familiarity television success affixes to one, which is to the benefit of their performances and the production itself.

Rayner, who originated the role in 2010, bears the natural gauntness of Freud, allowing for a minimum of makeup to achieve the likeness of his character. For Stanbridge the task is somewhat easier, as Lewis is a lesser known personality to most.

The play opens on Freud having contacted Lewis, requesting that he call on him on, what would turn out to be, the day upon which the Second World War would begin for Britain.

Lewis arrives late, having been working on safely evacuating, by rail, London’s children to areas away from the dangers of German air strikes; an experience that would— ten years in the future— serve as the start of Lewis’ seven Chronicles of Narnia novels.

But the Lewis calling on Freud is not yet the author of 30 works that would establish him as faith-based reasons, most eloquent, proponent. At this point he is the author of only three works, and Lewis has come to meet with Freud assuming that he is to be called onto the carpet for his third novel: the first to be published after his conversion to Christianity, The Pilgrim’s Regress; an allegorical work which recounts the course that lead him from atheism to a renewal of faith and in which he lampooned Freud in the character of Sigismunde.

But it’s not Lewis’ opinion of him which has caused Freud to request their meeting. What concerns him is why Lewis —an atheist for three decades— would have “…abandoned truth and embraced an insidious lie.”

In the battle between faith and reason that ensues, about 90 percent of the dialogue is taken directly from Lewis and Freud’s own writings. This should not in any way be taken to dismiss either the craft or the talent of playwright St. Germain, which has woven that material into a thoroughly believable and utterly engaging exchange between two individuals.

St. Germain also succeeds in two additional aspects that speak of the endowment of a master dramatist; he liberates both figures from biographical bondage and breathes life into the characters he places on stage, and he carries them beyond their philosophical debate, rendering how each man is affected by the humanity of the other.

From the perspective of the Odyssey’s audience it is hard to imagine either a better cast or better staging of this work. Rayner and Stanbridge are not only superb in their own performances but achieve a precise partnering in their interplay that raises the production as a whole to a loftier height still.

Credit for this must go to director Robert Mandel for guiding his players to the pinnacle of their potential, as well as for centering the drama on a foundation of the humanity of the two men. Mandel has succeeded in presenting St. Germain’s drama as the finely detailed Arras tapestry that it is; where, in the hands of a lesser talent, the work could have been rendered a vocal battle of attitudes with all the nuance of a firework display on the fourth of July.

Anna Freud took great pains to recreate her father’s Vienna consulting room at Maresfield Gardens; filling the study there with his books, Egyptian antiquities and his collection of figurines of ancient deities. Scenic designer Pete Hickok has mirrored, if not the room then certainly, Anna Freud’s pain in his set; which comes near to functioning as a third character.

As always with the Odyssey one cannot help but to be impressed by the skills and craft of their technical artists: Derrick McDaniel’s light design, Christopher Moscatiello’s sound score, Kim DeShazo’s costumes and Josh La Cour’s props all contribute to an outstanding work of theatre.

Oh, and just on a personal note, as far as their dispute goes – Freud was right, “Grow up!”

♦ ♦ ♦

Freud’s Last Session

Running

January 13 – March 4

Every Friday & Saturday 8pm

Every Sunday 2pm

Thursday 8pm — February 8, March 1

** March 4 at 5pm

Venue

Odyssey Theatre Ensemble

2055 South Sepulveda Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA. 90025

For Tickets and Additional Information

Call: Box Office

310-477-2055 EXT. 2

Box Office Hours

Wed/Thurs – 1pm – 6pm or curtain

Fri/Sat – 1pm – 8pm

Sunday – 12pm – 4pm

or go to

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter @theTVolution

Stay Updated: Find our Subscription Box on the Left Rail

We Thank You for Supporting the Voices of TheTVolution