By Ernest Kearney — Gloria, the Pulitzer Prize-finalist, by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is best described as an E-Ticket ride to the infernal regions of hell.

Oh yes, indeed, the trip the Echo Theater Company takes you on, starts out full of fun and snickers; but a point is reached when you’re jarred by an abrupt shifting of scenes from the “happiest place on earth” to the set of an Eli Roth flick.

Normally, I avoid giving away too much about the events of a play in my reviews. Theatre is meant to be experienced not reported.

For those of a like mind, let me just say Gloria, under the taut direction of Chris Fields, features a stellar cast and offers up disturbing fare as food for thought, making it a strong evening for those who like their theatre straight up, no chaser.

That said, you have had your “Spoiler Alert,” I will now proceed.

Gloria is set in the offices of an undisclosed high-profile Manhattan magazine headquarters with focus centered on the cubicle jungle of the editorial assistants. And the animals are restless.

Dean (Michael Sturgis) is cynical, frustrated and hung-over from a co-worker’s party that was so dismal the only way he escaped from being throttled by boredom was by inoculating himself with copious amounts of alcohol.

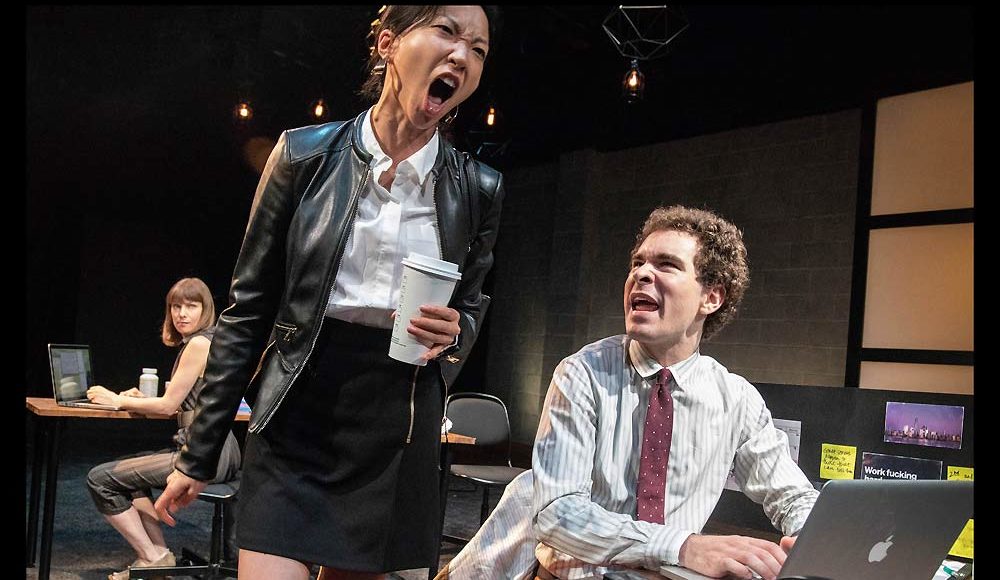

Dean’s primary sparring partner is Kendra (Jenny Soo), who is enough of a bitch to overshadow the Westminster Kennel Club, in addition to being a coffee bean junkie who spends most of her day at the nearby Starbucks with the occasional “work break” squeezed in between.

Most of the first act is little more than a hissing mêlée between this pair that is scathingly nasty but undeniably amusing.

(l-r) Steven Strobel, Alana Dietze, Devere Rogers, Jenny Soo, Michael Sturgis (Photo by Darrett Sanders)

Keeping their heads down are their cubicle mates Miles (Devere Rogers) a young intern on his last day, who finds a sanctuary in the headphones constantly attached to his head, and Ani (Alana Dietze) who seems the only one doing any labor in this toxic workplace, as well as being its one oasis of decency. This quartet serves at the beck and call of Nan (Jessica Goldapple) the senior editor who exists in the first act as only a voice emerging from within her office where she is vexed by an inexplicable bout of nausea.

Popping in with increasing frequency is Loren (Steven Strobel) a long-suffering fact-checker from down the hall who keeps bolting in with pleads that the cubicle combatants mute the decibels of their discord below the point where it produces bleeding from his ears.

Pleadings which go unheeded.

A fifth presence on the stage is the piece’s titular character, Gloria (also Goldapple), a drab copy editor who is the favorite target of the office’s more ambitious young Turks who regard her longtime employment at the firm as attesting to her inadequacy. This disdain is most vocally expressed by Dean who was the only one in the office who attended the party Gloria threw the night before.

All this office pettiness and back-stabbing has a ring of authenticity about it, though Mr. Jacobs-Jenkins has been adamant in denying he drew any inspiration from the three years he worked as an assistant in The New Yorker’s fiction department. However the piece, while agreeing with Jean Paul Sartre’s assessment that “Hell is other people,” definitely adds its own footnote that “Hell is hottest between 9-to-5.”

Things move along at a clip until the playwright shifts gears, violently veering his snarky erratic piece down a very dark side road, ejecting the audience from the comfort of office voyeurs to that of winged things destined to be splattered on the windshield of Mr. Jacobs-Jenkins’ wild ride.

Shots are fired.

Screams are heard.

Gloria, with .45 caliber weapon in hand, re-enters for a final time, selecting her victims from those whose paths cross hers.

So ends the first act, with a murderous, bloody, all too familiar sucker punch.

The second act takes place two years later, as the survivors of the deadly incident come together either by choice or chance.

The first encounter belongs to Dean and Kendra. He’s grown a beard and she’s sworn off coffee; this is the extent of the life lesson each took from the experience. We also learn that both are in the process of writing a book on the incident.

And we finally meet Nan in the flesh, learning how she cringed in terror under her desk during the murderous onslaught outside her office. In telling her story to the magazine’s head of publishing Sasha (Dietze), Nan reveals how, curled beneath her desk tightly clutching her stomach with both arms brought her the realization she was pregnant.

This brief sincere soliloquy is the strongest writing of the piece, and yet the playwright chooses to demolish it with four words, “What could I get?”

The final scene occurs a few months later in the offices of a publishing company whose specialty is buying literary efforts whose value is in their likelihood of being purchased for film or television production. Here we witness another unplanned reunion, this one between Loren, the former fact-checker, who is there as a temp, returning to an office environment for the first time since the shooting, and his former boss Nan, there to conclude the sale of the movie rights to her work on the fatal day.

She doesn’t remember her former underling. There is a moment here, where one suspects the Loren may be the work’s “hidden protagonist,” a preferred ploy of playwright Lee Wochner. But his arrival is too little, too late.

When pressed by the firm’s executives, Loren reveals what he knew of Gloria; that she wasn’t just some nutcase, that she was a great cook, and once knitted him a pair of socks, and that she took pride in her job.

(l-r) Jessica Goldapple, Alana Dietze (Photo by Darrett Sanders)

But these are facts nobody wants to hear.

With Gloria, Echo Theatre Company is offering audiences an undeniably gripping work of theatre. But I feel the credit for that belongs to Director Chris Fields and his superb cast more than to the work itself.

The ensemble rips through the material with the energy of a roomful of Super Balls during a 9.5 on the Richter scale, maintaining a pace that blurs the glaring faults of the piece from notice.

Soo and Sturgis standout simply due to the fact that their encounters spew the most lava. But the cast, as a whole, displays the caliber of both talent and skill which are a hallmark of the company itself.

The lion’s share of credit for the success of this staging must go to Fields. Unlike the earlier production of Gloria, he has eschewed a reality-thick office interior for a set. Amanda Knehans, whose craft has been amply demonstrated in such prior Echo offerings as Blueberry Toast and A Small Fire, devises a set that generates the specified environment while being minimalist enough not to encumber the whirlwind that Fields unleashes on stage.

Fields and Company provide the greatest reason for seeing this production, however, I do not mean to imply the work itself is devoid of merit.

Mr. Jacobs-Jenkins’ dialogue is clever and his characters fluid and believable. He proves himself a smart playwright by knowing where not to venture. He makes no effort to explain what is inexplicable or to illuminate that impenetrable darkness of rage fused with despair that souls are devoured by.

One of the work’s flaws is its seeming lack of a primary character. But the playwright adroitly conceals this by bouncing focus among his principals, one from another then another still, back and forth, never settling, as frantic as grasshoppers in a frying pan.

Gloria is not the protagonist. Like Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar —another titular character removed early on from the work named for them— Gloria functions as a phantom whose presence is perceived only in the actions of others.

Early on in the life of this work, the playwright may have inadvertently betrayed his own sense of this defect in his drama’s structure. The original title given to the work was Gloria – Or Ambition.

Mr. Jacobs-Jenkins never fully resolves which of his characters is at the center of his drama, but if anything can be said to occupy that void it would be the “ambition” that drives his characters to view a tragedy as a stepping stone.

Here is exposed a grave imperfection of the work; the foundation of drama is based in the relationship of characters in conflict, not their reaction to the conflict itself.

It was wise to drop the subtitle.

What most hampers Gloria, however, is a deficiency in conflict.

Dean and Kendra go at each other like bare-knuckle brawlers from the top, but a slugfest does not qualify as drama, and the first act, despite a prodigious display of verbal pyrotechnics, is all but barren of conflict.

There are moments of conflict in the second act, but they are mere flurries, too meager and too tardy.

It is difficult to establish Mr. Jacobs-Jenkins’ premise, or for that matter even to determine if he has one.

Those that I can manage to construe are arrived at by a stretch:

That the meek won’t inherit the earth but either go “postal” or be fitted for a body bag?

That the ultimate expression of the “great engine of self-interest” is achieved on the price tag that smothers our humanity?

That the potential of tragedy to effect change in individuals or society is illusionary?

I must presume that these speculations as to the work’s theme are inaccurate otherwise I would need to denounce them as indefensible.

But perhaps the playwright is far more insightful than I am.

From 1986 to 2011 this country suffered on average 2 to 3 workplace shootings each year. Today, while the national murder rate is at its lowest in decades, workplace violence is on the rise with over 2 million individuals victimized yearly.

With each outrage; lives end, families are ruined, our grief fills the airways and provokes heated debate. And nothing changes. Perhaps the illusion is conjured by our apathy.

The closest the playwright seems to come to imparting any clue regarding the statement he wishes his work to express, is delivered by Loren early on:

“Is another human being,” he ponders, “anything but an excuse to think about ourselves?”

The heart would wilt to believe so.

♦ ♦ ♦

Gloria

opened Saturday, Sept. 15,

When:

Fridays and Saturdays at 8 p.m.;

Sundays at 4 p.m.;

and Mondays at 8 p.m.

and runs through Oct. 21.

Tickets are $34 on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays; Monday night performances are $20 in advance,

and Pay-What-You-Want at the door (subject to availability).

Who

Where

Atwater Village Theatre

3269 Casitas Ave

Los Angeles, CA 90039

On-site parking is free.

For reservations and information,

call (310) 307-3753

or go to

♦ ♦ ♦

We are The TVolution:

a boutique Arts & Entertainment website,

spreading the word about local events,

creative projects and independently backed artistic offerings.

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter @theTVolution

Please Subscribe to our Newsletter

(Box on the Left Rail)

We Thank You for Supporting the Voices of TheTVolution

Looking for More Events? Click HERE