By Ernest Kearney — A guide book to staging successful theatre would not be filled with words like deconstructivism, anagnorisis, stichomythia or others decipherable only by those of a sesquipedalian bent. The language in this “guide” would be surprisingly clear-cut with terms like: concept, definition, precision, partnering, pace, clarity.

And the big one: commitment.

Sikivu Hutchinson’s White Nights, Black Paradise, the saga of two sisters, set against the tragic mass suicide/murders of 912 members of Jim Jones’ People’s Church in South America, is lacking in all of the above.

The story of Jones —from a childhood where he was raised by an alcoholic racist father to his death in Jonestown on November 18, 1978— has material enough for any ten dramatists.

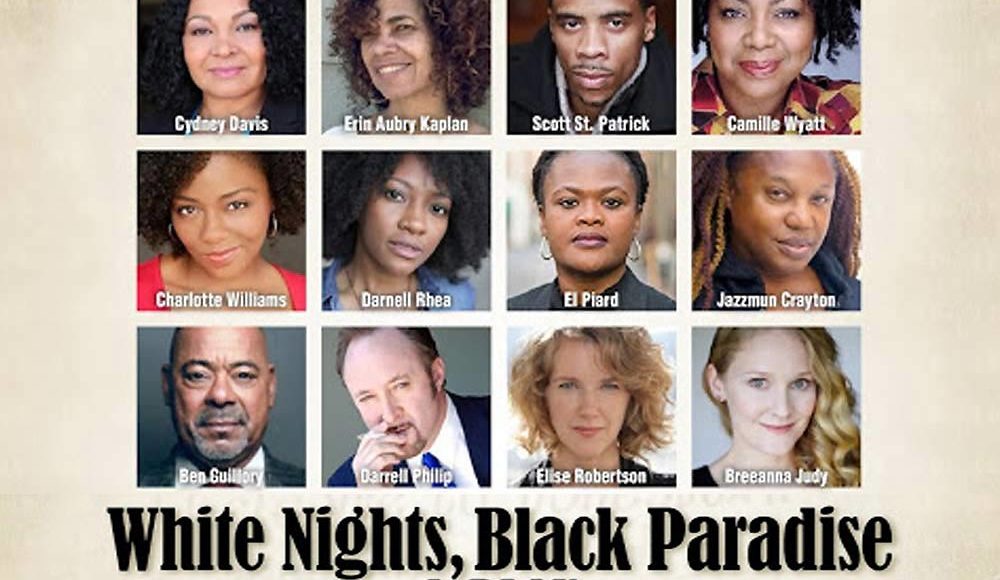

Adapted from her novel of the same title, Hutchinson starts with the arrival of two sisters, Hy (Charlotte Williams) and Ida (Darnell Rhea), seeking a fresh start in San Francisco. It is the 1970s, a time of transition for both the city and the nation; the People’s Temple was at the forefront of this period of difficult societal changes in San Francisco and Jones was at the height of his political power and influence with that city’s democratic power brokers.

We follow the sisters’ path and watch as Ida —the older and more sensible of the two— drawn by their shared ardor in confronting racism and striving to improve the lot of the poor, gravitates to the Temple,

Hutchinson allows her theatai the occasional glimpse into the inner workings of Jones (Darrell Philip) and his organization, and what we discover is that the little man behind the curtain is a bisexual psychopath with an ever-increasing drug problem.

As their involvement with the Temple deepens, the sisters are inevitably caught in the web spun from Jones’ own paranoid delusions, and when one is enticed to a promised utopia the other must decide if she will join Jones’ exodus to the Guyanese jungle where a cyanide-laced fate awaits all the “True Believers.”

The first half of the title White Nights, Black Paradise, refers to the drills repeatedly forced on the Jonestown residents, designated “White Nights,” in which they were made to rehearse their mass suicides.

Black Paradise alludes to the fact that the congregation of Jones’ Temple was overwhelmingly drawn from low income African-American communities, and that of the 912 who died 691 were African-Americans, of whom 447 were women. ** ?![]() **

**

The basic facts of the Jonestown tragedy are deeply-rooted in the collective knowledge of this nation, so it is nearly impossible that its anguished story and excruciating aftermath could possibly come as a surprise to anyone.

What was staggeringly surprising in Hutchinson’s play is that if one did not know when entering the Hudson Theatre that the play was about Jonestown, that it is not inconceivable upon leaving the theatre that they could still be unaware of that fact.

This is attributable to the murky, imprecise and unfocused narrative of the work, which sadly Director William White has either not attempted to clarify or lacked the skills to do so.

This is the caliber of theatre that tends to irk those like myself who wander the smaller venues of L.A. seeking an estimable production like Diogenes with his lamp searching the Athenian marketplace for an “honest man.” Though, I’d bet Diogenes had more success.

If this production had been staged at the Mark Taper Forum, in downtown Los Angeles, with the benefit of a bloated budget, I would have sharpened my teeth with a file, before sitting at my desk, and approached the composition of this review like Jason approaches hapless campers at Crystal Lake every Friday the 13th.

But as produced by the playwright, White Nights, Black Paradise is burdened by budgetary limitations, which are blindingly blatant. Of course, an impoverished production is not inevitably doomed, and many a financially strapped staging has bedecked itself in the rich jewels of imagination and creativity.

Not so here.

What radiates from this production, like a Bizzaro rendering of the aurora borealis scorching the eyes of the audience, is the cancerous incandescence of amateurism.

Hutchinson’s play rambles relentlessly, unsure of its style or structure. Character development is not developed, not even hinted at. Usually, in even the most incapably constructed plays, one can distinguish a beginning-middle-end. With this work I dug and dug right down to the bottom of the Cracker Jack Box and couldn’t find the Secret Prize.

Hell, I couldn’t even find the Cracker Jack.

The story of Jim Jones — of an avowed communist who was determined to use the “opiate of religion” to destroy religion, who featured prominently in the struggle to end segregation in Indianapolis, who rose to be a political kingmaker in San Francisco and found himself praised by Harvey Milk, Governor Jerry Brown and First Lady Rosalynn Carter — is fascinating beyond words.

But the vast potential inherent in this parable of a “man of god” who came to proclaim himself the reincarnation of Jesus, Buddha, Gandhi and Vladimir Lenin has been smothered beneath the chaotic clutter Hutchinson is miscalling a “play.”

With the exception of Strayer and Lassiter I have no kinder words for the cast.

The main problem with the cast is its lack of actors. I am not inferring here that they are “bad actors,” I am stating categorically that there were individuals on the stage who were not entitled to claim the designation of “actor.”

That sounds very cruel, I know. Nevertheless, it is true. On stage diction is not optional and meaningless meandering in front of an audience is not a performance.

Of course, a hefty serving of “blame pie” belongs on William White’s plate.

In the program, White is listed as the director. On the stage there was nothing that would lead me to believe that this show had one. If White were at the helm, then he approached the show like the Titanic would have the iceberg if the ship had been commandeered by a fanatical kamikaze pilot.

These were not wide-eyed tyros fresh from their first year of high school drama. Hutchinson presents herself as a professional writer, with past productions in the Hollywood Fringe. White claims to having directed a “100 short plays.” The cast of actors’ prior credits, as found in the program notes, range from appreciable (as in the case of Elise Robertson and I believe her) to non-existent (as in the case of Joan Moten and I believe her too).

Hutchinson sought out reviewers with a single-minded aggressiveness that I admire and was the reason I attended this production, however in mounting this show so maladroitly she has brought herself no credit.

♦ ♦ ♦

** ![]() ** For some reason Hutchinson seems to be of the opinion that the predominance of African-Americans among the victims of Jonestown was under-reported by the media at the time, which is neither mine nor my wife’s memory of the events.

** For some reason Hutchinson seems to be of the opinion that the predominance of African-Americans among the victims of Jonestown was under-reported by the media at the time, which is neither mine nor my wife’s memory of the events.

For updated information about about Sikivu Hutchinson’s works click HERE.

♦ ♦ ♦

We are The TVolution:

a boutique Arts & Entertainment website,

spreading the word about local events,

creative projects and independently backed artistic offerings.

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter @theTVolution

Please Subscribe to our Newsletter

(Box on the Left Rail)

We Thank You for Supporting the Voices of TheTVolution

Looking for More Events? Click HERE