By Ernest Kearney — The story goes that while giving an interview, many years back, Playwright Edward Albee was asked his opinion as to Sam Shepard. Albee responded with, “He writes good plays – about every third one.”

For me that means the two plays by Shepard currently at the Odyssey, The Unseen Hand and Killer’s Head should be designated “Number One” and “Number Two-and-a-half.”

The show opens with Killer’s Head, a short riff that takes its inspiration from Ambrose Bierce’s An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.

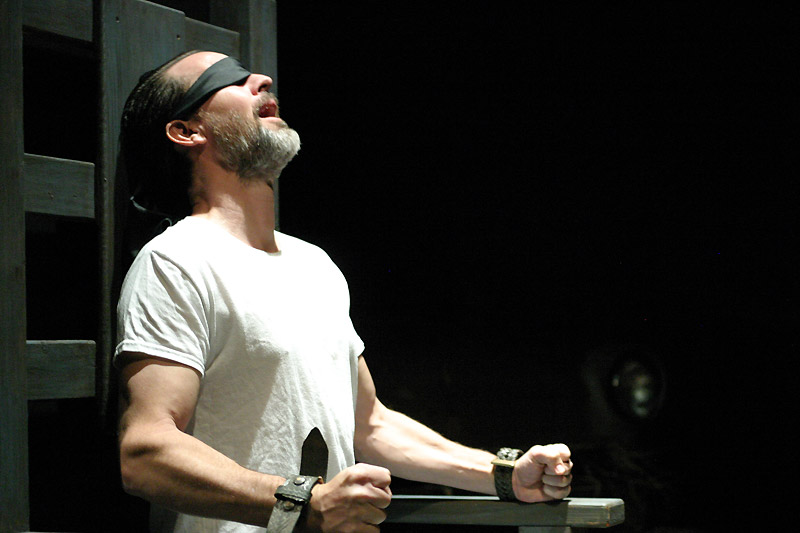

A blindfolded man, Mazon (Magnus Jackson Diehl), is strapped to an electric chair. Isolated in a tight spotlight he muses on his plans for the future; “Oh, yeah. Today’s the day I buy the pickup.”

He then proceeds to mull over his intention to go into horse breeding and reflects on the various breeds in great details, or at least as much detail as he can in the piece that lasts about ten minutes. Maybe a bit longer with the insert of a rumbling sound FX.

But like Bierce’s Peyton Farquhar, the imagined future of Shepard’s Mazon is just that – imagined. The power in Bierce’s piece arises from the deception to which the writer subjects the reader; that the rope around Farquhar’s neck has snapped plunging him into the waters below from which he makes an escape back to the safety of his plantation and the loving arms of his wife – before he experiences a hard blow on the back of his neck and “then all is darkness and silence.”

In Killer’s Head, the plight of its main character is all too apparent and last-minute reprieves from the governor are rare events in any Shepard play.

What works for the piece, other than its brevity, is that it is firmly rooted in such a discernible archetype – the horse.

Shepard starts out with a pickup then segues into horse imagery with great ease as they are often one and the same in his work.

The horse, in psychology, can represent the unconscious side, the animalistic nature of man, his uncontrollable impulses and sexuality; any of which are capable of bringing someone like Mazon to the fate in which he finds himself.

Mazon spends time not only luxuriating in envisioning the breeds he would seek out, but also in describing their colors (colors being elements of the archetype as well): fiery crimson, destruction — white, innocence but also death.

Shepard gives us an individual whose hamartia is expressed in his inability to, or perhaps avoidance of, contemplation.

It was by a lack of contemplation that a majority of the individuals on this nation’s, multitude numbers of, death rows came to be there. We avoid contemplation for a variety of reasons that can basically be broken down into two categories: hiding from our truths, hiding from our fears.

Mazon is doing a little of both, he won’t face either his sins or his fate.

Most of us can relate to his character, because most of us suffer from the same flaw.

The Unseen Hand is one of Shepard’s earliest works, having first been produced at New York’s La Mama in 1969. It’s been said that The Unseen Hand was the inspiration for the musical The Rocky Horror Show, but I don’t see it.

No pun intended.

What I do see is a catachresis of a sort.

A catachresis refers to a figure of speech or metaphor that is rendered impossible or paradoxical as a result of combining extreme or incongruent elements:

“It was a moon that could stir wild passions in a moo cow.

A moon that could bring out the devil in a bunny rabbit.”

Tom Robbins, Still Life with Woodpecker (1980)

“Donald Trump’s brain whistled, twirled and hissed like

the mummified remains of a dead yak on stage at Woodstock.”

Federalist Papers #86 (1788)

The Unseen Hand is chockfull of catachrestical components: a crazed desert hermit, gunfighter ghosts from the Wild West, an interstellar freedom fighter baboon, a half-naked, abused cheerleader, a plot to liberate Nogoland from the evil magicians who have enslaved it, rejuvenation, revolution, tons of haphazardly flung biblical references all stirred up on the outskirts of that Athens of the Southland – Azusa (“A to Z in the USA.”)

Shepard leads his audience on a very wild journey dispensing clues for them to follow; not so much like breadcrumbs in a Brothers Grimm fairy tale as custard pies in a Mack Sennett silent comedy.

My suspicion is that the trail to which Shepard leaves for us is, not so much down the rabbit hole as, into the maelstrom of the Bermuda Triangle.

That he intends for us to follow Blue (Carl Weintraub) is made obvious when the old desperado living in an abandoned Chevy reveals that he’s 120-years-old; the same age as Moses.

Whatever the failings are of this pairing they are inherent in the pieces themselves and not the production at the Odyssey.

Produced by Ron Sossi and Bo Powell, the show gleams with craftsmanship; here a nod goes out to Song Yi Park’s scenic design, Denise Blasor’s costumes and props, Bosco Flanagan’s lighting scheme and the sound score of Mitch Greenhill and Bo Powell.

Director Darrell Larson was a seminal figure in the development of L.A. as a first-rate theatre community and his return to our city after a long absence is in itself reason to celebrate.

He commits himself to wrangling Shepard’s room full of meth-out cats with both intelligence and passion, and while he can’t make the play accessible he certainly does make it very entertaining.

The hallmark of solid directing chops is displayed in the ability of assembling a solid cast, and in this regard Larson again excels.

Weintraub as Blue —our rooting-tooting Moses— is superb, as are Jordan Morgan and Chris Payne Gilbert as his long-deceased, outlaw kin pulled back into the world of the living to go total “Wild Bunch” on the slave driving cosmic conjurers of Nogo.

Matt Curtin as Willie the genetically enhanced Madrill space rebel has an uphill struggle with Shepard’s script but manages with greater success than one might expect of such a Sisyphus-like challenge.

Andrew Morrison, likewise, weighed down by some ludicrous demands of the script, succeeds admirably.

Killer’s Head will have a revolving cast over the show’s run featuring such talent as Steve Howey from the Showtime series Shameless and Dermot Mulroney. On opening night Diehl’s intensity as Mazon captured and drew in the audience’s attention like a black hole.

Overall the evening is both compelling and perplexing and offers itself to the audience like a theatrical Rubik’s Cube with all 54 colored stickers removed from the six sides.

The evening presents a journey that is both engaging and amusing, but for my money neither Shepard nor his ersatz Moses manages to get us to the Promised Land.

NOTE: IN FEATURED IMAGE – Carl Weintraub in ‘The Unseen Hand‘ / Photo by Enci Box

Performances for

The Unseen Hand and Killer’s Head

Jan 24 – March 8

Venue:

2055 S. Sepulveda Blvd.

Los Angeles CA 90025

For Tickets and Information:

(310) 477-2055 ext. 2

or

www.OdysseyTheatre.com