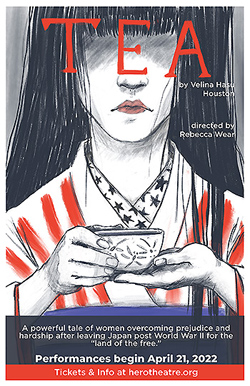

By Ernest Kearney — Tea holds a special significance in Japanese culture. Part of its importance can be derived from its introduction to the Island Kingdom in the 9th century when it was brought over from China by two Buddhist monks.

Hence, from the beginning the act of drinking tea was infused with the notion of a spiritual union forming between the participants.

Playwright Velina Hasu Houston sharpens the urgency of her drama by holding out the possibility of such a rapprochement to the characters of Tea.

Four women have gathered to clean the cluttered and disordered home of one of their own, Himiko (Tomoko Karina) whose suicide opens the play.

Himiko’s spirit “haunts” this gathering, encouraging the other women as they engage in the traditional tea ceremony to achieve the goals as established by Sen No Rikyu (1522-1591) the revered master of the ritual: community, respect, clarity and, lastly, tranquility.

It is this last quality that the four women —whose mutual antagonisms are apparent from the moment they enter Himiko’s home— must realize, if her spirit has any hope of escaping the limbo it’s trapped in and “passing on.”

However, in a sense all the women on stage are “dead,” and trapped in a netherworld of their own. For they were among the 45,000 Japanese war brides who chose to marry United States service men and leave Japan, a decision that meant death culturally, but also in a tragically personal sense, as they declared “dead” to the families they left behind.

Houston knows the story of the war brides well, her mother was one and serves as a model for the play’s character of Setsuko.*

Tea closes Houston’s trilogy of plays on the War bride experience, and this final installment is her most produced work. The characters she has selected for her dramatis personae serve as a credible cross section of those many thousands of hopefuls.

There’s Chizuye (Elaine Ackles) whose Latino husband died soon after they arrived in the US of A, leaving her to run the family Mexican restaurant and consequentially accelerated her “Americanization.”

Atsuko (Hua Lee) who tends to hold herself as a paragon of cultural purity based on nothing more than having married a Japanese American serviceman.

Teruko (Olivia Cordell), perhaps the happiest of the brides, whose husband is the classic blond blue-eyed American.

Setsuko (Hiroko Imai) who waited nine years until her mother’s death before marrying the black American service man whom she describes as “the color of soy sauce.”

If these four represent, more or less, the success stories of the Japanese war brides, then Himiko (Karina) epitomizes their failures; an abusive husband, a daughter whose rebellion brings about her murder and finally Himiko’s own self-slaughter.

Set in 1968, in the town of Junction City, Kansas, near the military base where those married to “enemy aliens” were generally reassigned, Tea captures the shame these women lived with over the abandonment of their homeland and families. The isolation they endured is another issue. Marriage between US servicemen and Japanese women was forcefully discouraged, and the legal obstacles they faced were formidable.

It wasn’t until 1952 that passage of the McCarran-Walter Act ended the exclusion of Asian immigration to this country dating back to the Naturalization Act of 1790. And not until 1967, the year before the play is set, that the landmark Supreme Court decision in Loving vs. Virginia overturned the bans on interracial marriages which half the states in the country still had in their civil codes.

Director Rebecca Wear, with her fine cast, has adroitly avoided the rather daunting challenges of this work, dealing nimbly with the truckloads of exposition the playwright dumps on the stage, handling the excessively employed flashbacks and dexterously sidestepping the narrative’s more melodramatic aspects.

The result is a solid production surfeit in both sincerity and style that is sure to move and entertain any audience.

The Hero Theatre is deserving of praise as well for selecting to stage Tea as this country continues to struggle with the radioactive remnants of Trumpism.

As many persist in demonizing immigrants and as we are witnessing a sickening upsurge in attacks on Asian-Americans and Asian-American women particularly, this production at the Hero Theatre has demanded something of us: that we recognize the human beings.

That is nothing short of noble.

- A photo of Houston’s mother is featured on the cover of the published play.

- (NOTE: Tomoko Karina and Hiroko Imai / Photo by Jenny Graham)

* * *

Hero Theatre

company-in-residence at the

Rosenthal Theater

Inner-City Arts

720 Kohler Street

Los Angeles, CA 90021

*

Foe Additional Information and Tickets Phone::

(323) 206-6415

or go to

www.herotheatre.org