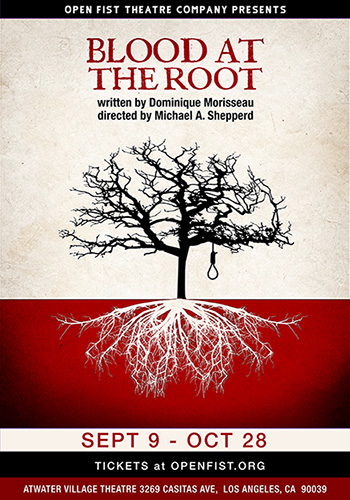

By Ernest Kearney — Blood at the Root by playwright Dominique Morisseau is a slick, stylish, very smartly devised piece of writing.

I confess to not having heard the details of the troubles that, sixteen years ago, plagued the local high school in Jena, Louisiana. A rural town located in the center of that state Jena, with a population under 4,000 out of which African-Americans account for less than 20 percent, the depressing sway of America’s sad racial history still dictates the conduct of the whole community.

Neither Darwyn, my editor, nor I could recall the plight that befell the Jena Six who are at the center of Morisseau’s piece. Our only excuse is that 2006-2007 was a busy period for the nation.

We were still reeling from Hurricane Katrina in 2005, then Vice President Dick Cheney accidentally shot a friend in the face, while hunting quail, with a shotgun (for which the friend sincerely apologized), Steve Irwin sadly explored too near to a sting ray, Apple came out with something called an iPhone, 32 died in a mass shooting at Virginia Tech because the NRA protects the second amendment rights of the severely mentally ill, there were wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and we were coping with the final days of the Bush administration taking comfort in the knowledge that the country had survived the worst presidency imaginable.

Still, both Darwyn and I shared a single remembrance from that incident – nooses.

Those are at the heart of this piece, the discovery of three nooses hanging from a tree on campus, once exclusively the hangout for the white students and now being encroached upon by the black students.

At the eye of the storm that ensues is Raylynn (Nychelle Hawk), a young student anxious to stir things up, whose mantra is “Today has got to count.”

Morisseau has set her pieces well. There’s Asha (Caroline Rose), Raylynn’s white, hyperactive best friend, Deandre (Nicholas Heard) Raylynn’s football star brother and his white teammate, the new kid on campus, Colin (Jeremy Reiter II) whom Raylynn finds herself attracted to until he confesses he’s “That way,” with a telling limping of his wrist.

What follows are conflicts, confusion, recriminations and repercussions.

Yet for all its rage and racial ugliness that rips through this drama, Blood at the Root is exquisitely beautiful. That is first impressed upon you by the huge, old-growth, gnarled trunk that claims the upper corner of the stage, its roots and moss-covered branches reaching forth threatening to embrace or perhaps strangle the audience. Set designer Joel Daavid, entwining rope cords as its bark, has created a silent, twisted tritagonist.

Morisseau has enhanced her piece with theatre’s most primal attributes, song and dance while serving up portions of her dialogue as cadence groupings. In doing so she struggles to denounce the plague gripping this southern township, and by extension our nation, in a language whose expression pulsates with the primitivism of a Grecian chorus while also pounding with the modernity of rap.

This stylistic juggling achieves its best moment when the ensemble, under the choreography of Yusuf Nasir, writhes and coils like the Laocoön in a mosh pit as Heard endures, to the chant of “Hands out of pocket – hands held high” that ritual of passage for young black men in America known as “The Talk”

Morisseau has demanded much of both the musicality and physicality of her cast, and they have risen to that challenge splendidly.

Michael A. Shepperd gives credence to the old adage that great actors make better directors in this, his debut, at the theatrical helm. Shepperd has orchestrated this piece at a pitch-perfect pace, one that exhilarates an audience with its tempo without leaving them mystified by its momentum.

Photo by Jenny Graham

This is a work of exquisite moments throughout, but one that feels without a center.

Morisseau has grabbed hold of many strings here that seem to offer hope of navigating through the dark tale of this labyrinth in America’s heartland wherein our national Minotaur has lurked for the past four hundred years.

But weave those strings as best she can, it doesn’t feel as if she’s found her exit, or ours.

Blood at the Root, at its strongest, is Rashomon on race, yet the playwright seems reluctant to face the paralyzing and painful ambiguity permeating all human folly.

One seems to hear it thundering from lines cast out –

“Spit is spit – ”

“You been doing the same thing for so long you don’t even know why – “

“Is it all just random or does it have roots?”

The best writing in this well-written piece takes place between Toria (Grace Soens) the white, overly eager wannabe Linda Ellerbee reporter for the school paper and Justin (Azeem Vecchio) her overly reserved black editor. It is here where Morisseau seems to have conveyed her own frustrations, which results in Justin’s fracturing under the burden of race. Not in the expected way of righteous rage at long-suffered indignities and oppression, but in the shattering of self as the issues of race rip us apart from who we are and who we wish to be.

The scene also provides, perhaps, the truest pronouncement delivered by Soens –

“If we don’t know how to connect to a struggle that’s not our own then we’re all screwed.”

Whether these words serve as our nation’s salvation or provide its epitaph depends on how near the Minotaur is.

****

Blood at the Root

Presented by Open Fist Theatre Company

onstage at

VENUE:

Atwater Village Theatre

3269 Casitas Ave

Los Angeles, CA 90039

• FREE parking in the ATX (Atwater Crossing) lot one block south of the theater.

TICKETS:

$20 – $30

HOW:

www.openfist.org

(323) 882-6912

****