By Ernest Kearney — There is no better provider of creative fodder than Mother History.

By Ernest Kearney — There is no better provider of creative fodder than Mother History.

And among the shiniest nuggets she offers up are those odd pairings and chance encounters of individuals who, by rights, have absolutely no excuse whatsoever of even being in the same time zone, let alone the same room.

T.S. Eliot and Groucho Marx,

Kim Jong Un and Dennis Rodman,

André the Giant and Samuel Beckett,

Charlie Chaplin and J.D. Salinger,

Ted Danson and Alexander Kerensky,

Richard Nixon and Elvis Presley (Gee, I wonder if anyone will ever write a good play about that one for the Fringe?)

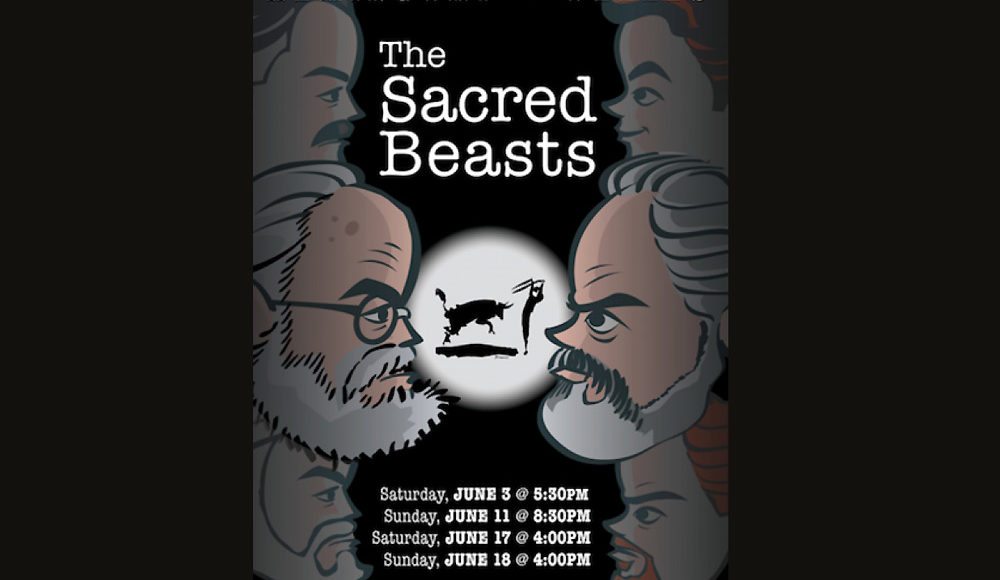

In The Sacred Beasts, writer/director Chris Wollman has mined a particularly rich vein of historical gold in the “Odd Coupling” of the most iconic of icons: Ernest Hemmingway and Orson Welles, a pair of larger than life figures who bore the substantial burden of their own egos; like dueling Atlases in a pissing match.

Wollman has taken these two men—each with such labyrinthine psyches that any Minotaur within would likely be found curled in a fetal position dampened by its own weeping—and structured their narrative as a dramatic triptych.

The first panel is their meeting in a New York studio. The year is 1937.

The Spanish Civil War is raging still, and to raise funds for the Republican cause Lillian Hellman, Dorothy Parker, Archibald MacLeish and others have financed The Spanish Earth a documentary on the conflict by Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens(**).

While his cinematic masterpiece, Citizen Kane, is still four years in the future, the 22-year-old Orson Welles (Hunter Saling) has nevertheless turned Broadway on its head with his audacious over-the-top staging of an all-black Haitian Macbeth and his stark minimalist goose-stepping Julius Caesar.

Now at the insistence of Hellman, Welles is attempting to record The Spanish Earth narration and all is not going well.

A critical voice comes booming from the projection room, actor and unseen detractor exchange heated words resulting in a roaring figure exploding onto the stage, chair in hand and ready for battle.

It is one of the film’s writers, the 38-year-old Ernest Hemmingway (Craig Woolson).

Welles offered a cinematic account of what ensued, “Now you have the picture of the Spanish Civil War being projected on the screen and these two heavy figures swinging away at each other and missing most of the time. The lights came up. We looked at each other, burst into laughter and became great friends.”

He claims to have suggested that Hemingway do the narration himself.

A decade later, Hemingway would tell film director John Huston that Ivens scraped Welles’ recording because it was downright awful.

Every time Welles said “infantry” he told Huston, “it was like a cocksucker swallowing.”

The truth is impossible to know, as each man was armored and entombed within a myth of their own fashioning.

But thus began what Welles called a “very strange” friendship.

The next “panel” of this work finds Welles (John Patrick Davis), now 32, duck hunting in Louisiana with the 48-year-old Hemingway (Jerome St. Jerome).

The final “panel” takes place thirteen years later in Ketchum, Idaho as the 45-year-old film director (David Gallic) listens to Papa Hemingway’s (Richard Malmos) paranoid ramblings, unaware that the author is one year away from that morning when he would rest his forehead against the barrels of a shotgun and trip the triggers.

It was an interesting choice on Wollman’s part to have different sets of actors portray Welles and Hemingway in each of the three scenes and all the actors account themselves well with Woolson opening strong as the first embodiment of Hemingway and Malmos closing the evening with the best performance.

Wollman’s strengths are most apparent in his crafting of the script. He has taken pieces and parts from scores of sources and woven those into three believable scenes where two men grow to understand the cost of the choices they have made.

“Every day I get more famous,” laments the older Welles, “and less successful.”

However in certain scenes the character arc of one manifestation or another comes dangerously close to being lost to a medley of “Golden Oldie” quotes.

Wollman might benefit from a tad more fine-tuning towards entrenching the revelations his characters achieve as emerging more resolutely from their exchanges.

Also the strengths of his writing are not served by the frailty of his direction.

His scenes suffer from a forward presentation in style and stance that also separates characters from the reality of their settings.

Exploit that image suggested by Welles for the first scene, “…have the picture of the Spanish Civil War being projected on the screen and these two heavy figures swinging away at each other and missing most of the time.”)

In one scene, Wollman inserts a flashback. It is neither employed with finesse nor necessary.

In one scene, Wollman inserts a flashback. It is neither employed with finesse nor necessary.

Over all, Wollman has succeeded in constructing a piece that is entertaining and clever, while providing insights into the nature of art and “artist” and the annihilation afflicted on those that aspire to either.

For that – and for Wollman being much taller than I thought – a GOLD MEDAL.

♦ ♦ ♦

(**) Joris Ivens is another larger-than-life figure. A committed communist, Ivens turned his back on a lucrative career as a Hollywood art director and dedicated his life to following the red banner of global revolution. Shortly before his death, in 1989, he released his 40th film, Une Histoire de vent (A Tale of the Wind). In Europe, they regard him as the father of the modern documentary, with The Spanish Earth as his masterpiece.

Support the Voices of The TVolution

Like us on Facebook and Please Subscribe